Sahar Boroomand, Dai Duan, and Mohsen Jaafarnia (2017). VIEWS OF FOREIGN OBSERVERS ABOUT IRAN, ABOUT THE FIRST CIVILIZATION. The People Museum Journal , Volume 3, Issue 1, ISSN 2588-6517

VIEWS OF FOREIGN OBSERVERS ABOUT IRAN, ABOUT THE FIRST CIVILIZATION

Sahar Boroomand

School of Art and Architecture, Central South University, Changsha, China

Dai Duan

Professor, School of Art and Architecture, Central South University, Changsha,

China

Mohsen Jaafarnia

Assistant Professor, School of Design, Hunan University,

China

The

Persians produced one of the great empires of human history which is in currant

Iran, but, at its fullest extent, the Persian king’s writ ran from Egypt or

Macedonia in the west to modern-day Afghanistan in the east. Founded in the

mid-sixth century BC in the breathtaking series of conquests of Cyrus the Great (Harrison, 2011).

But how do we know what the Persian empire was really like? When Persepolis was

excavated in the 1930s, a vast archive of administrative documents was

unearthed. These small, simple clay tablets have transformed our knowledge of

the everyday realities of Persian rule. We now know, for example, how the relays

of couriers, who carried messages for the king at supposedly superhuman speed,

were organized, and who was who in the Persian court. We also have a small

collection of the Persian kings’ pronouncements inscribed on stone – timeless

statements of the kings’ power and legitimacy in beautiful, austere language (Harrison, 2011).

History has always been the greatest teacher of mankind. Going through the views expressed by foreign writers about past civilizations leads us to a more advanced and experienced way in order to achieve our goals. Foundations and principles of those ancient civilizations are the best techniques to conclude a better way of living and basing our future. This section is only based on documented history.

The views expressed by foreign writers and historians on the eternity of Iran will be referred to this paper. Here we will limit ourselves to some of their general observations on the subject of Iran. Here we start first with L. P. Elwell-Sutton ((1912–1984) ,he was a scholar of Persian culture and Islamic studies. He was professor emeritus at the University of Edinburgh where he held a chair in the school's department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies. Elwell-Sutton was noted for a variety of published works on Persian language, Persian literature and folklore; modern Persian political history, and Islamic science. His 1955 book Persian Oil: a Study in Power Politics is noted as both influential and controversial), he says “... There are two factors which emerge from a study of Iran's long history and which must be continually born in mind. In the first place, in spite of constant invasion and conquest, she has always survived intact a solid and indigestible block. Secondly, she has shown herself capable of appreciating and absorbing new ideas and new influences without impairing her own basic culture.” also “Both these factors are the result; it would appear of Iran's vital position as the dividing Line between the East and the West. On the one side are the truly [Oriental] peoples of India and the Far East, with their introspective, individual attitude toward life and their Capacity for passive resistance. On the other hand are the Semitic and European races [for the Arabs have more in common with the West than with East]; their characteristics seem to be restlessness, aggressiveness, an urge to expand and to dominate their neighbors. Iran has drawn from and contributed to both these cultures without in any way losing her own individuality; no doubt it has been this cultural influence rather than any political strength that has enabled her to survive.” (Elwell-Sutton, 1941), in this way G. N. Curzon believes “If Persia had no other claim to respect, at least a continuous national history for 2,500 years is a distinction which few countries can exhibit.” (Curzon, 1892).

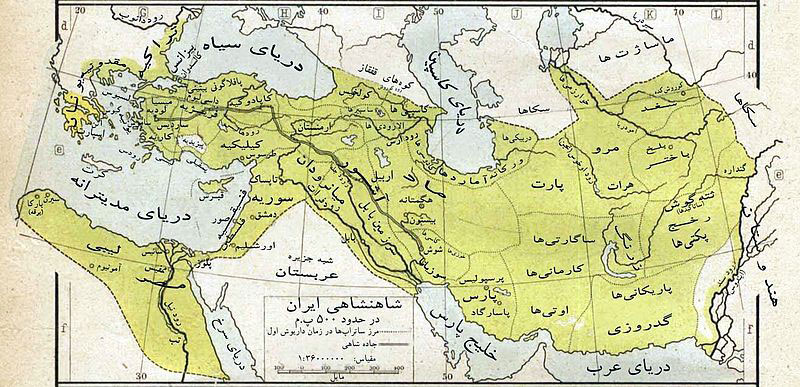

Figure 1. The Achaemenid empire map 1.

R. S. Morton thinks Iran has a lot of potential for research on civilization as he mentions “Iran’s survival gives us food for thought: Shall we of the West live three thousand years as it has done.” (Morton, 1946), also R. Grousset had written about Iran characteristics, he mentions “One of the characteristics of Iran is that it presents itself as the seat of one of the oldest civilizations of the ancient world, a civilization which, while constantly renewing itself throughout its history of almost fifty centuries, has proven to possess an astonishing continuity . . . The fame which thus became lit on the Iranian plateau at the dawn of history has never been extinguished. The appearance of the Macedonians was only an interlude, for Alexander, much more than he hellenized Persia, by proclaiming himself the successor of Darius and Xerxes “persianized” himself …” (Grousset, 1951) Grousset further notes “This unbroken continuity over so many centuries has permitted Iran to develop a profoundly human civilization, which, moreover, has appeared as such since its first historical manifestations.” (Grousset, 1951), based on these notes both the Iranians and Iranologists are persuaded that Iran’s ability to triumph over the cruelest and most destructive invaders of history must certainly bestow upon it the right to have faith in its own future and to consider itself eternal. The Macedonians have been erased from the face of history; not even a trace of Alexander’s grave remains. Islam is alive and expanding and yet Arabia was not able to maintain its domination for more than a century. On the contrary, Arabia returned quickly to the situation of the pre-Islamic period, known as the ‘Age of Ignorance’, and lost its importance except for containing the sacred cities of Islam, Mecca and Medina. Of the empires of Chingiz Khan and Tamerlane nothing remains but stories of slaughter and mass destruction (Nasr, 1974).

Figure 2. The Achaemenid empire map 2.

In The Cambridge History of Iran (which is a multi-volume survey of Iranian history published by Cambridge University Press. The seven volumes cover the history and historical geography of the land which is present day Iran, as well as other territories inhabited by peoples of Iranian descent, from prehistoric times up to the present.) We can read that “The uniqueness of Iran amounts to far more than a few outstanding textile designs, a cluster of medieval buildings, and volumes of lyric poetry. The visitor to Iran, if he is in any degree perceptive, soon becomes aware of an evolving yet firmly rooted pattern of life which, in its continuity with the past, retains much depth of tradition.” (Fisher, et al. 1989).

“With Iran ... one can recognize a clearly defined unitary response over many centuries to prevailing natural conditions ... And though maintaining its own identity Iran has been able to reach out to influence other lands. Some countries, as historians interpret the matter, have come into existence and are held together by virtue of a specific “Mission” for instance, they developed in response to the exigencies of a particular human situation. Austria defended Western European values first against the Ottomans, then less successfully against the Slavs; Spain resisted Islamic penetration through Africa; medieval Rome functioned as residuary legates of Imperial Rome …” (Fisher, et al. 1989).

“In no sense could Iran be regarded as merely a smaller or attenuate version of another stronger cultural or political area. Rather, it should be considered as an integral unit with its own institutions that contribute in a major way to the character and hence broader unity of the Middle East ... If we seek to define Iran's function as a state and as a human grouping in terms of a ”personality,” then the country can be said to generate, to receive and transmogrify, and to retransmit ! ” In the same connection it is further stated that “Iran has stood out as a highly significant polity of vigor and distinctiveness.” (Fisher, et al. 1989).

A. C. Pope has Measured history of Iran, he believes “Measured by the historic life of Iran, Greece seems but a glorious episode, and the grandeur that was Rome bur a single act in the world's drama. A phenomenon of such potency is a challenge to historical understanding. Not only Asiatic, but also world history is unintelligible until the source of Persia's power is discovered, expressed end measured and the extent of her influence estimated and comprehended.” (Pope, 1930); In the same way, E.G. Browne ((7 February 1862 – 5 January 1926) was a British orientalist. He published numerous articles and books, mainly in the areas of history and literature) is further stated that “ ... The power of national recovery. Few nations whose history can clearly be traced back for more than 2,400 years, who still possess their own contemporary records of some of the earliest events of that long period, have passed through and recovered from so many terrible vicissitudes as have the Persians.” (Browne, 1918).

During the latter part of the 19th century, when Iran's future was threatened by the pressure from two world powers, Russia and Great Britain, S. G.W. Benjamin ((February 13, 1837 – July 19, 1914) was an American statesman. Born in Argos, Greece, but then educated in the United States, he pursued careers as a journalist, author, and diplomat. In 1883, he was appointed as the first American Minister to Persia, a post he occupied for two years.) was commented as follows “In spite of the political corruption that has been practiced in Persia for many ages, she has contrived to exist for upwards of three thousand years, her people are as happy on the average as other people, and she continues to show great recuperative vitality; while a country like England, with a liberal constitutional government shows signs of decay within less than a thousand year, and the political corruption in our own country has reached such gigantic dimensions as to create in the minds of our wisest and most patriotic citizens an intense conviction of the absolute necessity of a speedy and radical correction of the evil.” (Benjamin, 1886) Reuben Levy ((28 April 1891 – 6 September 1966) was Professor of Persian at the University of Cambridge, who wrote on Persian literature and Islamic history. ) also mentions “Persia did not then (after the Arab invasion) or at any time, loses the identity which she had possessed almost from the beginnings of recorded history. The features making for her endurance were, of course, largely physical and geographical, but they consisted also in certain resilient and indestructible elements in the character of her people and their collective institutions. They remained identifiable even in the systems imposed by the Arabs, the conquerors who in historical times had left the greatest impress on the country,” (Levy, xxxx).

In the same way as these

scholars, others also talk about glories of Persian Empire and give

enough information about important facts of Persian to have a discussion just we

make a list of 10 facts about Achaemenid Empire here:

Fact 1: Cyrus The Great

Cyrus the Great founded the empire. In 550 BC, the Median Empire was conquered

by Cyrus. Then he conquered the Lydians and Babylonians.

Fact 2: the growth of the empire

The Achaemenid Empire grew larger under the next kings. They ruled Egypt,

Mesopotamia, Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and ... As, Achaemenid Empire could be the

largest empire on earth.

Fact 3: The Life Of The

People Under Cyrus The Great

The people were allowed to continue the practice of their cultures and lives

under the reign of Cyrus the Great. As long as the people obeyed the rules and

laws of the Persian civilization, they were allowed to keep their religion, way of

life and customs.

Fact 4: satrap

Satrap is an important position in Achaemenid Empire. Each area is ruled by a

satrap to maintain and control this big empire. In the modern world, you can

compare a satrap with a governor.

Fact 5: The Number Of

Satrap

The number of satrap in ancient Persia was around 30 satraps. Their main

jobs were to enforce the law of the Persian civilization.

Fact 6: the Royal Road

The Royal Road was the famous road in Achaemenid Empire. King Darius the Great

Built it. Actually there were many roads in the empire. It also had a postal

system. This Royal Road had the length of 1,700 miles. It spanned from Sardis,

Turkey to Suza Elam.

Fact 7: Prophet Zoroaster

Prophet Zoroaster is an important person for the Persians. The Persians followed

Zoroastrianism based on the teaching of Prophet Zoroaster. The main god based on

this religion is Ahura Mazda. But each culture was allowed to keep their

religion.

Fact 8: The Greeks

The Greeks and Persian had a battle under the reign of King Darius.

Fact 9: Fell Of Persian

Empire

The Persian Empire fell down after the Greeks could defeat it under the reign of

Alexander the Great.

Fact 10: Artaxerxes II

Artaxerxes II was the longest reigning Achaemenid king. His reign last from 404

till 358 BC for 45 years.

Conclusion

Here we have opinions of scholars but these are a few as we can not mention all here , but for the last one we would like to end this paper with A. U. Pope and Tom Harrison.

A. U.

Pope opinion as he says “How often has Persia disproved the gloomy prophecies

that her day was done. Evidently, Persia is immortal, and her destiny promises

to ride with humanity itself." (Pope, 1965). And in a

research of Tom Harrison (2011) who teaches ancient Greek and Persian history at

Liverpool University, say: "For a narrative of what happened, however, and for detail of court life, we are

dependent on the accounts of Persia’s enemies, and above all Greeks such as

Herodotus, the father of history, or Xenophon. As a result, reconstructing

ancient Persia presents special challenges. Can you rely on the Greek version of

events at all? Or is it somehow possible to sidestep the Greeks’ bias while

extracting worthwhile historical facts from their accounts?"

Historians still tend to take sides. Indeed, 2,500 years later, it is tempting

to imagine that the Persian Wars are still going on (Harrison, 2011).

The

Persian empire may have been built on conquest, but by comparison with its

near eastern predecessors or with Alexander the Great it was fundamentally

peaceful in nature. Persian art does not, in general, show us rebels prostrate

before the king but images of the peoples of the empire offering their cheerful

submission. Stories of the kings – or, more often, their wives and mothers –

inflicting hideous tortures and deaths on those they saw as rivals for the

throne are the product of Greek bias and misogyny. but in reality,

It is important not to be misled by the image that the Persian kings wanted to

convey. The images of Persian art suggest an inevitability and a timelessness to

their power. But there is no mistaking the threat of brute force under the calm

surface, or the pride that the king takes in conquest for its own sake. “If now

you shall think,” declares the Persian king Darius in one inscription, “‘how

many are the countries which King Darius held?’, look at the sculptures of those

who bear the throne… then shall it become known to you: a Persian man has

delivered battle far indeed from Persia!” (Harrison, 2011).

As for stories of cruel torture, we can only rely on probability. History shows

us plenty of monarchies in which lack of accountability leads to extreme

violence. Can we really exclude ancient Persia?

If the

Persians, rather than the Greeks, had come out victorious in the Persian Wars of

the early fifth century, it would have killed western civilization dead. It was

the bustling, democratic atmosphere of cities like Athens that gave rise to the

best of Greek literature and culture, but a Greek satrapy of the Persian empire

would inevitably have been a grey and conformist place. According to the

historian Anthony Pagden: "Had [the Persian king] Xerxes succeeded… there would

have been no Greek theatre, no Greek science, no Plato, no Aristotle, no

Sophocles nor Aeschylus". In fact,

Would a Persian victory have made so much differences? And is it only prejudice

that tells us democracies have more vital cultures? There is evidence that

the king would not have trampled all over the political systems in place in the

Greek cities, as long as they did not cause trouble. After crushing an earlier

revolt of some Greek cities, the Persians in fact toppled a group of tyrants and

introduced democracy. And for the vast majority of Greek cities, it was never a

simple choice between submission to Persia and outright independence. These

cities, most of them tiny, operated in the shadows of their larger neighbors,

their power of action vastly restricted. A change in the background power might

have made little difference.

The Persian king liked to present himself as a kind of global policeman, sorting

out the squabbles of other peoples. We should, of course, be skeptical of such

claims, but it is possible that some Greeks – weary of their constant local wars

– may just have seen some benefits in Persian rule. So would a Persian-backed

peace in fact have enhanced Greek creativity?

Unlike some other empires (Rome, say, or Britain), the Persian empire never set out to establish a single, universal way of doing things. It never sought to impose a common language or common religion on its subject peoples, but followed the principle of ‘live and let live’, of tolerance of different religions and cultures. As a result, if you are looking to judge the impact of Persian control on the peoples of the empire, you should not expect to see strong cultural influence of the sort that Rome had on the Mediterranean world. in fact, the truth is that the Persian kings could not realistically have imposed an universal religion or language over such a diverse empire, even if they had wished to. When they were in Babylon or Egypt, the kings behaved – at least outwardly – as if they were themselves Babylonian or Egyptian. But this approach was probably shaped by pragmatism rather than principle. A balance between clear displays of force and championing the status quo was an effective way of maintaining their power, and getting on with what all empires do in varying ways – exploiting the conquered.

References

Benjamin, S.G.W. 1886. Persia and the Persians. Boston: Ticknob & Co., PP. 165, 166.

Browne, E.G. 1918. “Address at the British Academy,” in the Proceedings of the British Academy. Feb. 6, 1918. Vol. VIII, London: Oxford University Press.

Curzon, G.N. 1892. Persia And The Persian Question. London: Longmann Green & Co., P. 6.

Elwell-Sutton, L.P. 1941. Modern Iran. London: George Roulledge and Sons, Ltd., P. 234.

Fisher, William B., Ilya Gershevitch, Ehsan Yarshater, Richard Nelson Frye, John Andrew Boyle, Peter Jackson, Laurence Lockhart, Peter Avery, Gavin Hambly, Charles P. Melville (eds.) 1989. The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Vol. I, PP. 737 and 740. ( 1 - 1).

Grousset, R. 1951. The Introduction to L’ame de L’Iran. by G. Contenau, Paris: Alben Michel, P. 7.

Harrison, Tom 2011. Writing Ancient Persia. Bloomsbury

History Extra. 2011.The Persian empire: myth vs reality. The official website for BBC History Magazine and BBC World Histories Magazine. https://www.historyextra.com/period/the-persian-empire-myth-vs-reality/

Lecoq, Pierre 1997. Les inscriptions de la Perse achéménide . Paris: Gallimard .

Levy, Reuben xxxx. The Leg. of Persia, P. 60 (1 - 4).

Morton, R.S. 1946. A Doctor’S Holiday in Iran. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co., PP. 331 & 332 ( 1 - 9).

Nasr, Taghi 1974. The Eternity of Iran. Tehran: The Ministry of Culture and Arts publication.

Pope, A.U. 1930. A Survey Of Persian Art. Vol. 1, P. 37, printed by Manafzadeh Group in Tehran, London & Tokyo, 1965 - First ed., London: University Press.

Pope, A.U. 1965. Iran American Review. New York: a publication of Iran American Chamber of Commerce.

![]()

© 2017 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).