Mohsen Jaafarnia, He Renke, and Sahar Boroomand (2019). IRAN FROM THE APPEARANCE OF MAN TO THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION. The People Museum Journal , Volume 5, Issue 1, ISSN 2588-6517

IRAN FROM THE APPEARANCE OF MAN TO THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION

Mohsen Jaafarnia

School of Design, Hunan University, China.

He Renke

School of Design, Hunan University, China.

Sahar Boroomand

School of Art and Architecture, Central South University, Changsha, China.

The definition of the term civilization has changed many times during its history. It is commonly used to describe human societies with a high level of cultural and technological development. Etymologically, civilization relates to the Latin term civitas, or ”city”, which is why it sometimes refers to urban societies, setting aside the nomadic people who lack a permanent settlement and those who live in settlements that are not considered urban or do not have an organization. In a wide sense, civilization often means nearly the same thing as culture or even regional traditions including one or more separate states. In this sense, we sometimes speak of the “Persian civilization”, “Chinese civilization”, or “Egyptian civilization”, but each of these may include several cities or regions.

WHERE AND WHEN DID MAN APPEAR?

Man’s curiosity has been a source of his weakness as well as his strength. All his knowledge as well as his superstitions has derived from it. Being self-centered, man has for thousands of years sought to know when, where and why he has come into being. And what is his destiny. Over the centuries, peoples have answered these questions in various ways, and have defended their answers to the last breath. But no final answer has been found (Nasr, 1974).

Over a million years ago manlike creatures (Hominids) had evolved. These early Hominids had ape like faces, were short in size and small in brain but walked almost erect. They had no spoken language as yet but already knew how to use stones as weapons and tools. It took the hominids some five hundred thousand years to learn how to walk fully erect hence the expression Homo erectus), to develop a language, to make better stone tools and to use fire. Then again another five hundred thousand years elapsed until man attained the status of Homo sapiens (wise men) which he has today (Nasr, 1974).

In the course of this slow evolution the men like creatures spread from their original habitats, in Africa to other parts of the world, and “of necessity via the Middle East” (The Cambridge History of Iran, 1968). One of the oldest remains of man found in the Middle East are from the Jordan River valley and date back more than 300,000 years (Field, 1956; Coon, 1962).

A group of well-known contemporary scholars, including H. Field, believe that these first men lived at least 100,000 years in the Middle East “during which time rapid cultural advances occurred.” There homo sapiens developed about 50,000 years ago and began to migrate in every direction (The Cambridge History of Iran, 1968). Field adds that Ellsworth Huntington was convinced that some 25,000 years ago Iran was one of the most “ideal places in Eurofrasia for mankind”. Field calls Central Asia and Africa the “cradles” of man and Southwest Asia his “nursery” (Field, 1956).

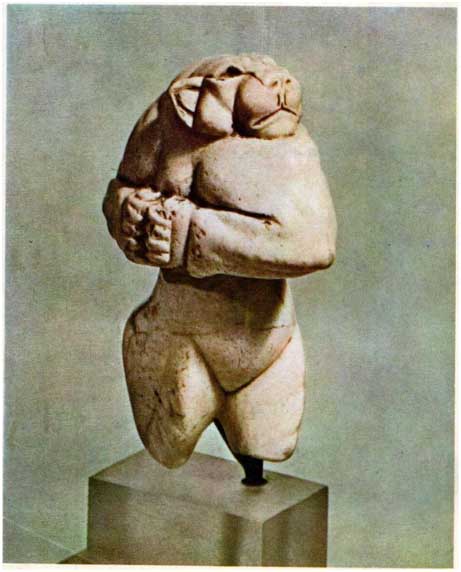

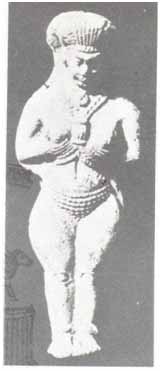

Figure 1: A clay figure, height 6. 15cm.,found in Tepe Sarah, near Kermanshah. Made about 6000 B.C .

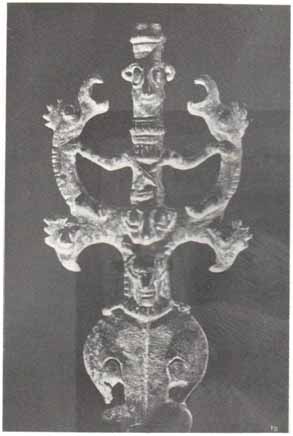

Figure 2: A demon limestone, Susa, about 3000 B.C. Height 8.4 cm

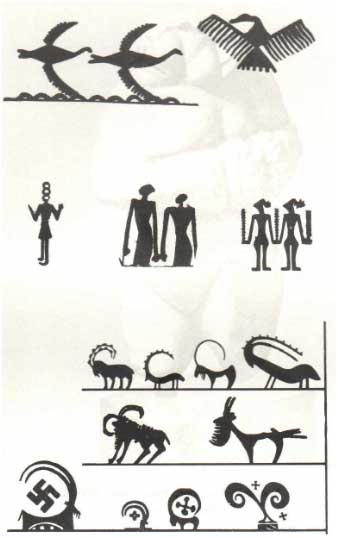

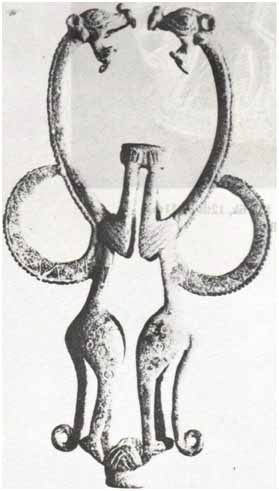

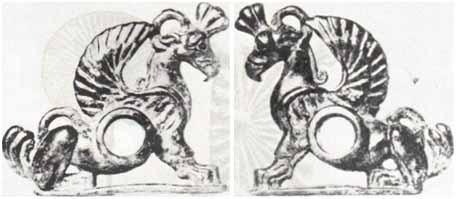

Figure 3 & 4: A few specimens of designs on vases in clay, 4500 - 3000 B.C. No other civilization has produced so many local styles and so many schools of rich decorative designs. Prof. L. Vandenberg (1968).

In any case, approximately 50,000 years ago, or taking into account the great diversity of opinion on this matter, 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, Homo sapiens reached the present form through biological evolution. Thereafter began the process of cultural evolution. What distinguishes the contemporary man from his ancestors of some fifty thousand years ago is cultural and not biological. Although one group of scientists believes that cultural evolution is itself genetic, and that so-called social-behavior always has a biological basis (Darlington, 1969).

Figure 5:. Lamp, grey pottery, Astarabad.

Figure 6: Figurine, terracotta, Astarabad, 2500-1500 B.C.

Is it not surprising that almost seven hundred years ago the Muslim philosopher Ibn el-Arabi calculated that the thinking man is forty thousand years old? Not only he had reached a conclusion very close to that of today’s scientists with none of the today’s tools and techniques for research (Rechid, 1926).

MAN BEGINS TO CONTROL NATURE

For over a million years, everywhere and in all the stages of his evolution man lived as a predator. His survival depended entirely on what he could obtain by fishing, hunting and gathering of roots, leave and fruits. His way of life, as that of animals, was totally conditioned by nature. Then about ten thousand years ago some small groups of earth's inhabitants began to find out how to domesticate animals and practice agriculture. At about the same time or a little earlier these “progressive” minorities had learned to make better pottery, build better houses, do some weaving and grind and polish their stone implements for greater efficiency. For this last technological advance the emerging era is called the New Stone Age (the Neolithic period) to distinguish it from the preceding one, the Old Stone Age ( late Paleolithic) during which only chipped stones were used (Nasr, 1974).

By the domestication of animals and cultivation of food plants man began to change from a predator to a producer. This change affected man's life-style and outlook to such a degree that archeologists qualify it as a revolution. Man had begun to control nature. From then on the growth of this control gives the measure of man’s progress. In this respect the flight to the moon and the conquest of space only continue the revolution which began when man domesticated his first animal and planted the first seed.

The progressive pioneers who begun the domestication of animals and agriculture lived in the Middle East, and probably not more than eleven or twelve thousand years have passed since the day that man ate his first home grown food (Nasr, 1974).

THE BIRTH OF CIVILIZATION

Let’s start here with Upanishad “Into blind darkness pass they, who worship ignorance, into still greater darkness they who are content with knowledge.” (Upanishad , 1954).

Several thousand years again passed before man reached a fundamentally new stage in his development, that of building cities. Some forms of divisions of labor had already existed in the previous stage, but in the cities, division of labor took new forms and was intensified. Professional governing bodies and priesthoods developed and arts, crafts commerce and the like were taken up by different groups. No longer farmers produced all of their own necessities or consumed all that they produced. Rather, part of their produce was exchanged in various manners for the services performed by city dwellers. Individuals faced new relationships and responsibilities and at the same time found new reasons for disagreement and discord. More important than all other developments of this period was the invention of writing (Nasr, 1974).

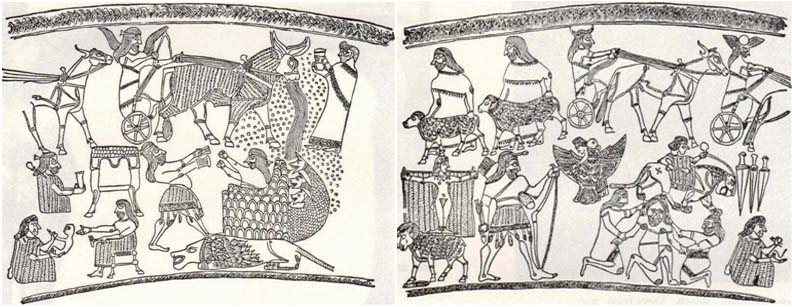

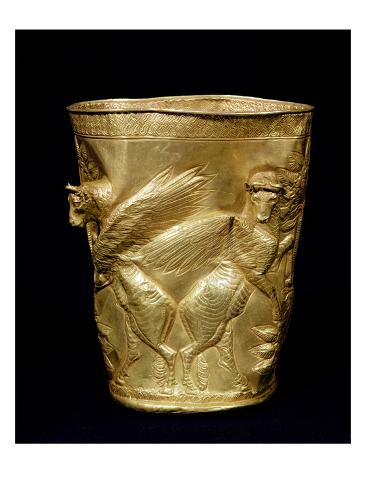

Figure 7 & 8: Designs on the sides of a gold bowl, Hasanlu, 12th-11th century B.C.

While these various developments mark the beginning of civilization, the invention of writing separates ”history” from “Pre-history”. On the basis of the evidence found so far it is generally concluded that civilization began from 5,000 to 5,500 years ago, though some historians extend these dates by another 500 years (Nasr, 1974).

The invention of writing is undoubtedly one of the most important and fundamental achievements of mankind. But just as today man is fearful of change; it seems that in the beginning he was not happy about this invention. According to Egyptian mythology, when the god Thoth revealed the art of writing to king Tbamos, the king complained that “Children and young people who had hitherto been forced to apply themselves diligently to learn and retain whatever was taught them would cease to apply themselves, and would neglect to exercise their memories.” (Durant, 2010).

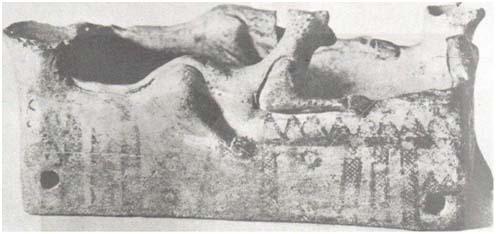

Figure 9: Some of the earliest writing symbols,4500-. 3800 B.C., probably the signs marked on the Fig. X means = God, XX = water and XXX earth Tepe Yahya

To the traditional questions as to where, when and how began the civilization is added today the question, why man undertook the struggle for progress? The conclusion reached by the anthropologist Geza Roheim on the basis of Freudian theories is quoted here as an indication of a current approach to the study of this subject: “Civilization originates in delayed infancy and its function is security. It is a huge network of more or less successful attempts to protect mankind against the danger of object-loss, the colossal efforts made by a baby who is afraid of being left alone in the dark” (Roheim, 1971).

Figure 10: Painted pottery Nihavand end 2nd millennium B.C.

The more relevant and more immediate question is, however, what is or could be expected of “progress”? Where is man heading now that he is or believes to be master of his destiny? An increasing number of thinkers complain with Bergson that “Mankind is growing, half crushed beneath the weight of its own progress.” There are even many highly respected social scientists who would like to slow down or stop altogether the technotronic race that enslaves the contemporary man (Club of Rome, 1971). But this question, extremely relevant as it is, is outside the scope of this study (Nasr, 1974).

THE CRADLE OF CIVILIZATION THE MIDDLE EAST

W. Durant (2010) says: “In studying and honoring the Near East we shall be acknowledging a debt long due to the real founders of European and American civilization.”

Five to six thousand years have passed since the birth of civilization. In the first half of this long period the center of civilization was the area that in its eastern reaches included the Indus River Valley and Turkistan and in its western, Egypt. This whole area is often referred to as the Middle East by students of ancient history (Nasr, 1974).

On the Iranian plateau, in the Nile Valley and in the territories situated between the two regions, man reached the stage of city-dwelling and civilization between five and six thousand years ago. In the Indus Valley this stage was reached several centuries later and in the Yellow River Basin in China, 1,500 years later. The Greeks and the Romans began building cities from 2,300 to 2,500 years after the inhabitants of the Middle East. A civilized society was established on the Island of Crete approximately 4,000 years ago, but it neither lasted sufficiently nor came to possess a distinct enough cultural identity to be considered separately in the present brief work (Nasr, 1974).

Figure 11: Gold beaker from Marlik,12th or 11th Century, B.C.

W. Durant: “Written history is at least six thousand years old. During half of this period the center of human affairs, so far as they are now known to us, was in the Near East. By this vague term we shall mean here all southwestern Asia south of Russia and the Black Sea, and West of India and Afghanistan, still more loosely, we shall include within it Egypt, too, as anciently bound up with the Near East in one vast web and communicating complex of Oriental civilization. In this rough theatre of teeming peoples and conflicting cultures were developed the agriculture and commerce, the horse and wagon, the coinage and letters of credit, crafts and industries, the law and the government, the mathematics and medicine, the enemas and drainage systems, the geometry and astronomy, the calendar and clock and zodiac, the alphabet and writing, the paper and ink, the books and libraries and schools, the literature and music, the sculpture and architecture, the glazed pottery and fine furniture, the monotheism and monogamy, the cosmetics and jewelry, the checkers and dice, the ten-pins and income-tax, the wet-nurses and beer, from which our whole European and American culture derive by a continuous succession through the mediation of Crete, Greece, and Rome” (Durant, 2010).

A. U. Pope (2005) mentions: “Agriculture, metallurgy and the initial religious and philosophical ideas as well as the art of writing and the science of numbers and astrology and mathematics originated in the lands that today we call Middle East, and the origin of many of these cultural elements is in the plateau of Iran”

Considering the influence of the Middle East on the progress of mankind in the rest of the world, E. E. Herzfeld (1941) writes: “Such continental connections are clearly outlined and will eventually become an accepted fact. The unity of Asia, though rarely achieved in its political history, is a real factor in the history of its civilization and even Europe will appear more and more as only a subcontinent of Asia. For prehistorical problems this means that eventually the entire chronology of European prehistory must be synchronized with the phases of Asiatic developments.”

IRAN “THE CENTER OF PRE-HISTORIC CIVILIZATION”

E. E. Herzfeld (1941) mentions: “For the Iranian Plateau, by its natural geographical position is the point of junction through which all movements that ever crossed the great Asiatic continent must have passed and always did pass.”

Our knowledge is still too scanty to enable us to say for certain when, where, and under what conditions and forms man first reached a civilized level of existence. The following excerpt from a study by a professor of anthropology, N. J. Berrill, supplements the information given in the previous pages: “Human history in the modern sense begins with the setting of small Neolithic villages in a Mediterranean belt of western Asia seven to eight thousand years ago ...” He defines this area as the southern shore of the Caspian Sea. From that area ”As the population grows it spreads outward from the periphery... But as the fringe moved slowly into distant regions the more stable and flourishing people of the heartland progressively developed their culture. Society at home carried the arts and craft of village life to higher levels while the small colonies of tribes penetrating the rims of their little world carried with them only the culture they possessed at the time of their earlier departure ... At about 3,000 B.C., possibly five or six hundred years earlier, Neolithic people arrived at the strait of Gibraltar, having followed their pigs almost acorn by acorn for the better part of two thousand years, but taking close on two thousand years to make the journey.

Some of them managed to cross the straits to continue the slow infiltration through Spain to settle in France and the British Isles. While another spearhead moving out of Asia Minor settled in Greece, Crete and Italy. Others again took a northwesterly course around the Caspian Sea and Black Sea to follow the banks of the Danube finally to reach Germany and mingle with the migrant wave that had come from North Africa through Spain. Both branches carried with them the technique for making soft pottery and for making black stone axes. Improved techniques also traveled the paths of migration as later folk continued to emigrate but at about the same pace so that painted pottery for instance reached Germany by traffic along the Danubian corridor about a thousand years after it had originated in the Caspian homeland.”

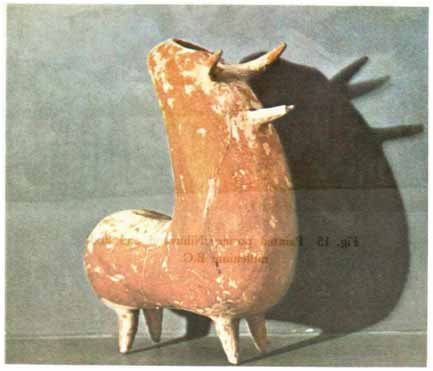

Figure 12: Vessel in the shape of a hull south western Caspian region ( ?) 12th or 11 Century B.C

“The same steady pressure of people from the Caspian basin took them into the highlands of Afghanistan, through the Kyber Pass and down into the Indus Valley, and took others across Turkistan to the upper Yellow River Valley, leading to China and eventually through Korea to Japan. All along these routes traces of the slender boned white Caucasian race still exist, in its blond or in its darker form.”

“… if you picture a spoked wheel, the hub represents the Caspian homelands, the rim the outer fringe of migrating explorers and the spokes the great rivers ... along which the most permanent settlements were established.”

For several thousand years ”since the end of the ice age” the earth was steadily warming up until about 5,000 B.C., when the thermal maximum was reached. That was when “the great migrations were underway possibly because of preceding drought”... This was a period decidedly warmer than at present which lasted from 5,000 B.C. to about 3,500 B.C., and was moister as well as warmer than the thousand years which proceeded it or the thousand or so that followed.”

“The drying out which made lower Mesopotamia once again inhabitable during the middle of the fourth millennium made the lands to the east of the Caspian Sea so dry as to be practically useless.” Then people moved westward to better places ... “So that the tribes who moved south into the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates at the time carried tales of woe and punishment, having been compelled by a better armed race to leave luscious lands that they loved. Here is the expulsion from Eden and the angel with his flaming sword who stood guard against their return.”(Berill, 1962)

In the Caspian region near the city of Behshahr a large cave was discovered in 1941, now called the Belt Cave (Ghare Kamarband). Dr. Carlton S. Coon, who excavated the cave, writes (1957)”By 9,500 B.C., this cave was dry enough for habitation,and it was occupied' by hunters who mainly killed seals, on or near shore,and who had already acquired two of the principal assets of the Mesolithic life (Or middle stone age) for instance, the bow and arrow and the dog. For some reason they departed, and after about 3,000 years circa 6,500 B.C.,other Mesolithic hunters, pursuers of the goitered gazelle, occupied the cave. These gazelles were, apparently, domesticated. In the Neolithic Levels the bones of sheep and goats bore a high ratio of immature specimens, twenty-five per cent in the pre-ceramic and fifty per cent in the ceramic strata. This meant that the animals were domesticated, because hunters rarely kill the young. The gazelles' bones were nearly all those of mature animals of domesticated type.” (Ghirshman, 1954).

Coon and a number of other scholars believe that the pottery found in the Belt Cave represents the oldest pottery which has yet come to light, and that the Caspians were the first people in the world to reach the stage of agriculture. Related to this issue E. E. Herzfeld (1941) mentions: “There is strong circumstantial support for the hypothesis not only that Caspians [The inhabitants of Iran before the arrival of the Aryans are not yet fully identified but are often grouped under the general name of "Caspians”. The Caspian sea, of course, takes its name from them (Herzfeld, 1935). ] of the early fourth and fifth millennia were agriculturists, but even that they were the original agriculturists, and that the knowledge of agriculture spread from the Caspian plateau over the three adjoining alluvial lands: The Indus, the Syr and Amu Darya, and the Tigris and Euphrates”.

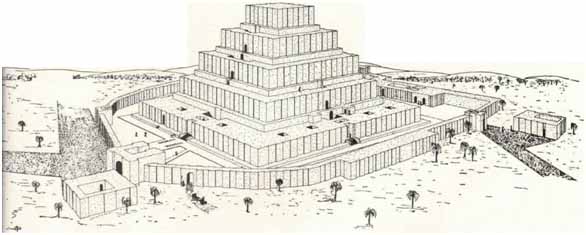

Figure 13: Chogha Zambil, plan. Earliest known Iranian monument“of imposing dimensions and character rivals the pyramids of Egypt. Built about 1250 B.C., dedicated to the great god “Lord of Susa" - height 165 feet. A.U. Pope (Pope, 1965).

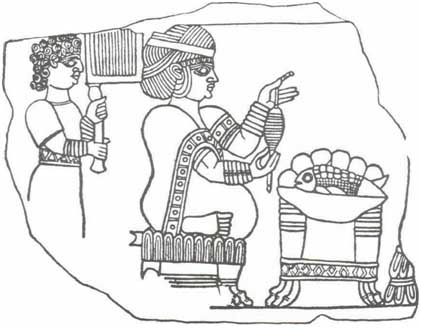

Figure 14: Relief from Susa, 9th century B.C.

Between seven and eight thousand years ago rural settlements existed in Iran in several places including Siyalk near Kashan, the plain of the present Marvdasht in Fars, and an area near Susa, the oldest surviving city in the world. At Sialk,”the oldest human settlement” identified so far on the Iranian plateau (Huot, 1965) are found just above the original soil level traces of man’s first occupation, when he did not yet know how to build houses. In the layers above, however, some remains thought to belong to the fourth millennium B.C. reveal that Sialk's inhabitants had discovered weaving, the use of metal and the seal, and that probably they had also invented the potter’s wheel (Grousset) .

R. Grousset writes:”... In the painted pottery ... Iran not only plays the role of the central agent but has also chronological priority”. Huot says, the excavations of the French archaeologist-scholar Morgan at Susa indicate also that ”south-west Iran was one of the first centers of painted pottery” (Huot, 1965).

Figure 15: Painted pottery, Sialk 1100-1000 B.C

Figure 16: Tumbler, painted pottery, Susa,2nd half 4th millennium B.C.

Figure 17: Figurine, terracotta, Susa 2nd and 1st millennia B.C.

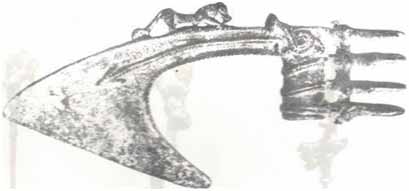

Similarly, Herzfeld states that the Caspians “were the original metallurgists” (Encyclopedia Britannica) and others believe that «the importance of Iran as a center of metal working in the ancient near east is evident from the so-called Lorestan ( Luristan) bronzes” (Ackerman, 1940). The unanticipated culture revealed by these bronzes is, according to Phyllis Ackerman, “exciting enough in itself) but ... (it) held added significance to historians of Iran … The Luristan art represents one phase of the Iranian preparation for that great (the Achaemenid) achievement, and thus is an additional link in the chain which binds human culture into a continuity for a good six thousand years.” (Delougaz).

Figure 18: Talismans, bronze, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millennium B.C.

Figure 19: Talismans, bronze, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millennium B.C.

Figure 20: Cheek plaques of bits, bronze, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millennium B.C.

Figure 21: Axe-head, bronze, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millenium B.C.

Figure 22: Frontal, Speculum, bronze, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millennium B.C.

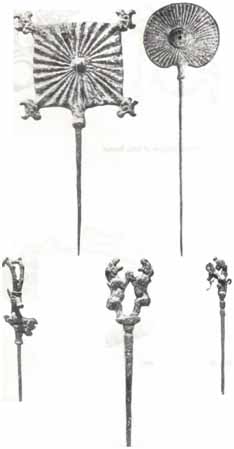

Figure 23: A few pins, metal work, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millenium B.C.

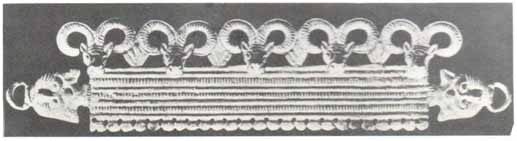

Figure 24: Armlet, gold repousse, GOLD OBJECTS, LURISTAN 2nd - 1st millennium B.C.

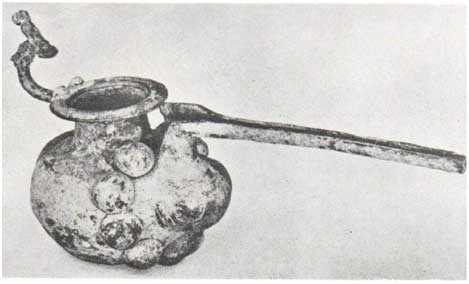

Figure 25: Spouted pot.

Many years ago at Chogha Mish, near Susa in Khuzistan, a clay tablet and a number of seals were found, where dates have been determined as of 3400 years B.C. On one of them is engraved a picture of the oldest known musical group, the members of which include a vocalist and the players of several instruments, including the harp, an instrument resembling the Persian setar the drum and trumpet (Coin World, 1972).

Figure 26: Design on a piece of clay. The earliest trace of musicians playing as a group ( an orchestra), 3400 B.C., found in Chogha Mish, Khuzestan.

A joint team of American and Iranian archeologists, under the leadership of C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, which began work in 1967 at Tepe Yahya, (The oldest level of habitation in Tepe Yahya has been estimated to date from 4500 to 3900 B.C.) has discovered a new center of civilization. At this site which is located in the South-East of Iran, approximately 60 miles from the Persian Gulf, 600 Miles from the Indus River Valley and 600 miles from Mesopotamia were found a building designed for administrative work, a number of seals and pieces of decorated pottery, as well as tablets that contain cuneiform scripts mostly related to commercial transactions. It is believed that civilization started in this area at the same time as Mesopotamia and the other Middle Eastern centers, and that very probably this center had relationships with Mesopotamia and to a lesser degree, with the Indus Valley (Nasr, 1974).

Another team headed by Dr. David Stronach, director of the British Institute of Persian Studies, conducting archeological research since 1967 has recently found some silver and ring pieces at tapeh Nush-i-Jan some two hundred miles southwest of Tehran. These silver pieces believed to have been marked with finesse and issuer's stamps, are considered as the oldest currency known. They were made between 760 and 600 B.C. (Mundi, xxxx; McCown, 1942; Childe, 1967).

The growth of civilization on the Iranian plateau influenced peoples in areas as far away as Turkistan, Baluchistan, the Indus River Valley and Mesopotamia (Herzfeld, 1941). In 1907 pottery and traces of the cultivation of wheat, barley and millet as well as of the domestication of animals and of the use of copper were found in Anau, located in Southern part of the present Turkistan. These finds indicate that the culture of the people of this area had made substantial progress long before the fifth millennium B.C.

The three cultures of Anau, Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley “show many points of similarity, and the relative positions of three indicate almost conclusively that the common source must have been on the Caspian highland” (Pope, 1945). In turn the influence of the Caspian highland spread through Anau to China, Manchuria and North America. The Neolithic pottery of Hunan province in China is almost identical with the stone-age pottery of Susa and Anau (Nasr, 1974).

Figure 27: Location of Hunan in China.

A. U. Pope says “In the light of the data recently discovered it has been proved that agriculture and perhaps the crafts attached to it, for instance pottery making and weaving, originated in the Iranian plateau. From several essential points, the civilization in this area began 500 years before Egypt 1000 years before India and 2000 years before China” (Lloyd, 1961).

The Sumerians, who are known as the pioneers of civilization in Mesopotamia, according to Seton Loyd “were the first to arrive in the drying marshes of the head of the Persian Gulf, and they came down from an earlier home in the Iranian Highlands, where their remoter part merges into a pattern of pre-historic migrations” (Genesis). The book of Genesis refers to the same event in the proverbs: “and it came to pass, as they journeyed from the East that they found a plain in the land of Shennar and they dwell there” (Vandenberg, 1968).

AGRICULTURE AND LIVESTOCK

As in the other countries of the ancient

Orient, the problem of water was crucial in the Persian Empire, with the

exception of a few rare, privileged regions. Because of this, the peasants put

together perfected systems of irrigation. Canals were excavated for the

conduction of water, as well as wells and subterranean galleries, similar to the

“qanats” of present-day Iran, to avoid, in the aridest regions, excessive

evaporation (ACW, 2017).

In this way, the ground was revalued and grains like barley and wheat were

cultivated above anything else. On the other hand, the raised great flocks of

horses and bovines, as well as donkeys and camels. Horses were nearly all for

riding, while donkeys and oxen were used for working the fields: making the mill

wheels turn, or pulling wooden plows, equipped with a metal point, which served

for tilling. The lands belonged, sometimes, to independent peasants, who, in

cooperative groups, worked the lands of various families. The other lands

belonged to the nobility, who ceded its operation to settlers, being left with

part of the harvest (ACW, 2017).

Because of the lack of water and vegetation in this country burned by the sun,

the Persians gave great importance to gardens for recreation, whose supreme

luxury consisted in being scored with innumerable small streams, sprinkled by

fountains and full of flowers. The tradition of gardens has been conserved, on

the other hand, in this area of the world, not only throughout all of the

ancient times, but also during the Middle Ages, in Muslim Persia, and in modern

times. Important hunting preserves, favorite sport of the nobility, starting

with the king, were likewise available, in the form of parks: they called them

“paradises.” (ACW, 2017).

It is not impossible that religious factors originated this lack of interest in

activities which produce the transformation of material. Commerce flourished,

especially in the interior, thanks to the important system of roads. In addition

to the royal road from Sardis to Susa, numerous highways crossed the Empire in

all directions, as much in the Asian interior as in Afghanistan or in the Indian

Provinces.

Of course, their trace had been made, above all, to satisfy the political,

military and administrative necessities of the Empire, but they were also made

use of for commerce as well. On these routes, whose distances were measured in

Parasangs (each Parasang was equivalent to a little more than five kilometers),

lodgings had been established which, according to Herodotus, impenitent

traveler, were excellent (ACW, 2017).

The roads had, in addition, the advantage of being safe, a very rare thing in

ancient times. “The royal roads, which they traverse continually, united the

most distant capitals of the Empire, Sardis and Susa (2,500 km.), in a record

time of approximately a week.”

apart from road design the imperial

administration was made up of various officials to connect each part of this

civilization system. in this way they could create Satraps, Secretaries

and Inspectors .

Satraps were Persian nobles who were at the head of a province or satrapy. They

represented the king in the province and considered themselves united to him by

a knot of fidelity in defense and administration of goods. They occupied

themselves with the collection of tributes, the maintenance of permanent armies

and with mobilizing the population to cooperate in public works. They were

considered the highest judicial authority in the territories in their charge.

Secretaries completed the functions of royal advisers of the satrap. The king

named them directly. Among their responsibilities was found that of

investigating the governor of the province.

Inspectors formed a body of auditors who controlled the interests of the king,

watching the satraps. They were called the eyes and ears of the king because

they informed him of all that happened in the empire and if his orders were

carried out. If the circumstances called for it, they could dismiss the satrap.

In synthesis, the imperial policy followed by the Persians tried to reconcile

unity with diversity, respecting, on the one hand, the regionalisms in culture

and traditions, and imposing, on the other hand, a centralization in the payment

of tributes and the provision of military services, decisive elements for their

survival.

Conclusion

This research shows the Legacy of the Ancient Persian Civilization which are:

Politics: The idea of a universal empire, an

objective recreated by many nations in the course of human history.

Economy: Generalization of the use of money in commercial transactions.

Intellectual Life: The idea of the struggle between good and evil and man’s

freedom of choice in choosing between the two.

Ethics: Tolerance towards conquered peoples.

References

1- The Cambridge History of Iran (1968). Vol. I, P. 395 (1-1). Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition (October 1, 1968)

2 - Field, H. (1956). Ancient and Modern Man in Southwestern Asia, 2 Vol., Miami Press, 61, P. 164.

3 - Coon, Carlton S. (1962). The History of Man, London, Jonathan Cape, P. 26.

4 - Darlington, C.D. (1969). The Evolution of Man and Society, London.

5 - Rechid, A. La quintessence de la Philosophie de Ibn-i-Arabi, Paris, Mohammed Ali Aini,Trans. (1926), PP. 66 - 67.

6 - Herzfeld, E.E., article in A Survey of Persian Art, Vol. I, P. 46 ( 1 - 20).

7 - Herzfeld, E.E. (1934). Archeological History of Iran, The Schsweich lectures of the British Academy, London, 1935, Oxford University Press.

8 – Upanishads (1954). quoted by will Durant, in Vol. I, P. 552 of the Story of Civilization, 10 Vol., N.Y. Simon and Shuster.

9 - Durant, W. (2010), quoted from G. Maspero, Dawn of Civilization. Simon & Schuster

10 - Roheim, Geza (1971). The Origin and Function of Culture, N. Y., double day.

11 - The Limits of Growth, sponsored and published by the Club of Rome, 1971.

12 - Pope, A.U. (2005). A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present, Vol. I. P. 5 ( 1 - 20). Mazda Pub (March 30, 2005)

13 - Herzfeld, E.E. (1941). Iran in the Ancient East, P. 7. London, 1941.

14 - Berill, N.J. (1962). Man’s Emerging Mind, Conneticut, PP. 187 to 201.

15 - Coon, Carltons S .(1957). The Seven Caves: Archaeological Explorations in the Middle EastP. 149- London.

16 - Ghirshman, R. (1954). Iran: From the Earliest Times to the Islamic Conquest.

17 - Huot, J.L. (1965). Archeologia Mundi, Persia from the Origins to the Achaemenids, PP. 79, 82 & 105, translated from Russian by H.S.B. Harrison, Geneva, Nagel.

18 - Grousset, R. , A Survay of Persian Art. Vol. I, P. 60 (1-20).

19 - Huot, J.L. , Vol. I, P. 105 (1- 46).

20 - Encyclopaedia Britanica, Article on Archeology of Iran in Encyclopaedia Britanica, Also Herzfeld, P. 51 (I-33).

21 - Ackerman, P. (1940). The Luristan Bronzes, The Iranian Institute, N.Y., P. 17.

22 - Delougaz, Pinhas of the University of California according to the translation of his article published in the Persian Magazine Khandaniha, No. 35.

23 - In the Magazine, Coin World, Sidney, Ohio, 1972.

24 - Mundi, Arch. , Vol. I, P. 115 ( 1-46).

25 - McCown, D.E. (1942). The Comparative Stratigraphy of Early Iran.

26 - Childe, Gordon (1967). What Happened in History, Penguin.

27 - Pope, A.U. (1945). The Masterpieces of Iranian Art, The Dryden press, P. 5.

28 - Lloyd, Seton (1961). The Art of The Ancient Near East, P.P. 19, 20, N.Y., Praeger.

29 - Genesis, Book XI, verses 2 & 3.

30 - Vandenberg, L. (1968). in the Magazine Archeology Vivante, Vol. ,.

31 - Pope, A.U. (1965). Persian Architecture, Thames & Hudson, London, P. 18.

32- Nasr, Taghi (1974). The Eternity of Iran. Tehran: The Ministry of Culture and Arts publication.

33- ACW (2017). Ancient Civilization of Persia. https://ancientcivilizationsworld.com/persia/

![]()

© 2019 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).