Mohsen Jaafarnia, Ji Tie, Sahar Boroomand, Avinash Shende, Mohsen Saffar Dezfuli and Seyed Hashem Mosaddad (2021). Medieval Design Travelling: Widespread Sassanid trade footprints on the Silk Road from Spain to India and China. The People Museum Journal , Volume 7, Issue 1, ISSN 2588-6517

Medieval Design Travelling: Widespread Sassanid trade footprints on the Silk Road from Spain to India and China.

Mohsen

Jaafarnia

Associate Professor, School of Design, Hunan University, China.

Ji Tie

Professor, School of Design, Hunan University, China.

Sahar Boroomand

School of Art and Architecture, Central South University, Changsha, China.

Avinash Shende

Industrial Design Centre, Indian Institute of technology Bombay, India.

Mohsen

Saffar Dezfuli

School Of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science &

Technology, Tehran, Iran.

Seyed Hashem

Mosaddad

School Of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science &

Technology, Tehran, Iran.

This research is funded by “National Key R&D Program of China No. 2019YFB1405702

Introduction

The history of product design is almost as old as mankind. With the course of time however, designed has evolved and it has transcended boundaries and cultural intricacies; as man developed Maritime/Land Silk Route, the art and culture of each nation has traversed geographically. Design had travelled from one place to another and a concise look at evolution and development of product design through the history brings to light many such cases. Several cultures surviving in isolation with distinctive art forms, speaking different languages and using different mediums began to be influenced by others and there has been interplay of cross cultural design motifs. Persians were competent in weaving fine silk and design metal wares and since time immemorial, Indian make jewelry and gems, Chinese make silk and molded ceramic ware. The link between these three civilizations were interestingly established by traders who, having realized that profits could be made exploiting such technical/ geographical gaps, wittingly or unwittingly, exchanged merchandises and led to spreading out of ideas.

Innumerable records have shown that after Islam made an entry into Persia, Islamic art was displayed in Sassanid art properties mainly through Persian artists who conceptualized and formulated beautiful geometric pattern [1]. These developments occurred because of Islamic rules pertaining to art in Arab society which led to evolution of the Sassanid geometric patterns. These eventually became the most significant art forms in Islamic cultures.

However in case of India and China, the story is different. Indian and Chinese have long histories of art and design, reveals that the exchange between Persian, Indian and Chinese cultures was not a one way process. Researchers have traced high level of inspirations on Indian, Chinese and Persian artworks, largely interchangeable in nature and bearing distinctive features of their bilateral relations reflecting the rich art forms of these three cultures. Regarding this one can see how the emulation of Indian and Chinese decorative motifs, such as the elephant, phoenix and dragon that bore traces of inspiration as it appeared on Persian product design decoration. In these products (Fig. 1. A and B) if one does not follow the figure caption, it is impossible to distinguish them as Persian pieces.

Figure 1. A, Bowl with Dragon motif, fifteenth century CE. Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1932 (32.33); B. Bowl with elephant and Phoenix motifs. fourteenth Century CE. Kashan, Iran. Ilkhanid period.

The Sassanid Empire was the major power in the West and Near East for 400 years. They sustained relations with the Tang Dynasty of China, Kushan and Gupta empires of India and also the West. Regarding their relations, the famous Chinese traveller, Huan Tsang, has mentioned “all they [the Persians] make the neighboring countries value very much.” [1] in another case Jawaharlal Nehru who was the first Prime Minister of India stated in his lecture about the nature of Chinese and Persian bilateral relations, quoting Can K’ien, a Chinese general sent out by emperor Wu to Fargana, Sogdiana and Bactria; that “He astounded his countrymen by his accounts of the Persian civilization and products which he brought back from Persia. The Chinese, although great artists themselves or because of it were fascinated by the Persian art”[2]. many samples were found near Turfan in Central Asia, displaying the popular images, design and symbols of Sassanid culture [1].

The important Sassanid achievement was seeking cultural and art travelling and the special attention given to the Academy of Gundeshapur. This academy was one of the most important centres of learning in the world’s history as it sought texts from all of the neighboring countries, for instance from Indian manuscripts, to Persian Zoroastrian texts. Many scholars were travelling from abroad and these round trips could spread cultural and art into the West and East [3]. For instance Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians to the Chinese imperial court. This shows, like their predecessors the Parthians, the Sassanid Empire maintained active relations with India and China. Evidences show Chinese were interested in Persian art [4]. But this cultural interchange did not, however, spread Sassanid religious practices or attitudes to those cultures. While the Sassanids always adhered to a stated policy of religious proselytization, and sporadically engaged in persecution or forced conversion of minority religions.

Commercially, land and maritime trade was important for the Sassanid, the Indian and the Chinese empires. All empires benefited from trade along these Silk Routes, and shared a common interest in preserving and protecting trade. A large number of Sassanid gold coins of different kings have been found in Southern China (keeping in Shanghai Museum); and early Tang Dynasty coins were excavated by David Whitehouse in Siraf in Southern Iran (keeping in the British Museum)[5], all confirming the existence of Sassanid maritime trade. Sassanid goods, including silver, glass, brocades and other items, with Sassanid design were carried by merchants to the East and West and it was during that time that Sassanid motifs were adopted by Eastern and Western craftsmen as ornamentation on wall painting, silk weaving, ceramic wares and brocades as derived from a few exotic pieces [6]. Although Sassanid political control did not reach beyond the Pamir mountain range in Central Asia; but the cultural footprints of the Sassanid Empire (AD 224-651) extended far into East side of Silk Road; The same footprints have been seen in the Westside of Silk Road [1].

Going by all these influences of Sassanid Art on neighbors, we see traces of Sassanid art along the Silk Route where researchers have often found themselves intrigued and bewildered whether discovered products originated from Persia or its neighbors. In our research, the aim is to trace and narrate the nature of the influences, by observing and connecting the Sassanid footprints on Indian, Chinese and Islamic design. For this, a comparison between their products and Sassanid products apart from the date of production gives a good perspective of the element of design exchange.

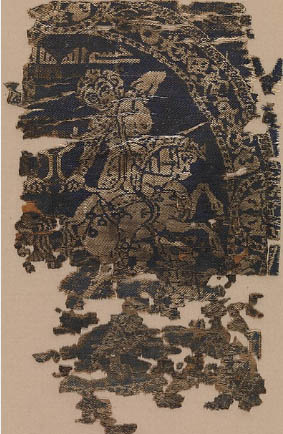

Hunting Lion

Hunting Lion is the first trace of footprint which was a common pattern used by East and West frequently on their product design. The evidences relate to design of these products consisting of hunting lion that is reflected in the motif of hunter on horseback or camelback, where the hunter turns his backside with bows and arrows originally related to Sassanid art. This is perceived as a common pose of Sassanid kings showcasing a shooting lion as part of their culture. This fact could be traced from the discovered products that could have been a borrowed design from Sassanid products [7]. This Sassanid pattern was diffused westwards and eastwards to India, China and to Japan through China [8].

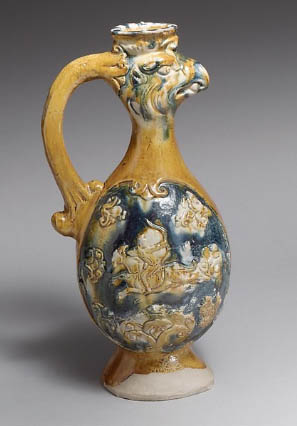

Figure 2. A. Medallion Depicting Addorsed Amazons on Horseback, sixth–seventh century CE. Sassanid, Made in Syria. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1927)27.58.1; B. Brooch Decorated with medallion, mounted lion hunter and three beads pendant in the middle, nineteenth century CE. Rajasthan, India. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1953)53.167; C. Patterned woven cloth with medallions with four mounted lion hunters, tenth century CE. Sung Dynasty. China. Silk Brocade; Chengdu Brocade Weaving and Embroidery Museum; D. Phoenix-headed ewer, seventh–first half of the eighth century CE. Tang Dynasty. China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1991)91.253.4.

Figure 3. A. Fragment, sixth-seventh century CE. Sassanid, Attributed to Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1890)90.5.855; B. Plate showing Shapur II (King) hunting lions, fourth century CE. Sassanid. Iran. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. S-253; C. Pommel Plate from a Saddle, thirteenth - fifteenth century CE. north India or Central Asian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (2010)2010.336; D. Textile fragment of hunting scene, eighth century CE. Attributed to Egypt or Syria. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1951)51.57.

Figure 4. A. Spanish Textile, first half twelfth century CE. Attributed to Spain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1958)58.85.2; B. Silk fragment, sixth-seventh century CE. Sassanid. The Victoria and Albert Museum, 8579-1863; C. Fragment of textile with horses, fifth–seventh century CE. Sassanid, Central Asia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (2004)04.255; D. Fragment, tenth–eleventh century CE. Attributed to Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1987)1987.440.5.

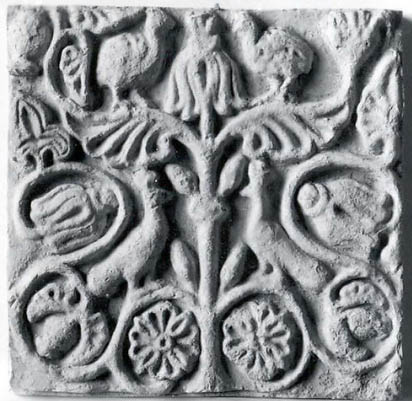

Figure 5. A. Wall panel with a guinea fowl, sixth century CE. Ctesiphon. Sassanid. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1932)32.150.13; B. Bowl, twelfth century CE. Attributed to Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1964)64.247; C. Sassanid motif wall painting, sixth-seventh century CE. Cave 60, in Kizil Grottoes, Xinjiang, China. Museum of Asian Art, State Museums in Berlin. Acquisition #MIK III. 8419; D. Textile fragment with a large circular medallion design, tenth century CE. Gujarat, India. Ashmolean Museum, EA1990.686.

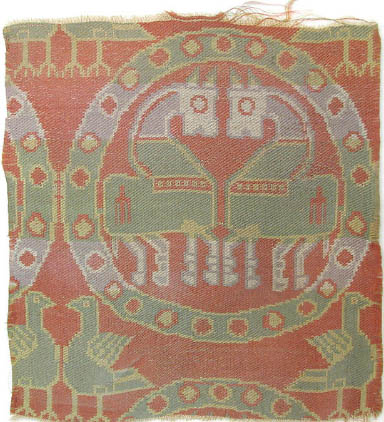

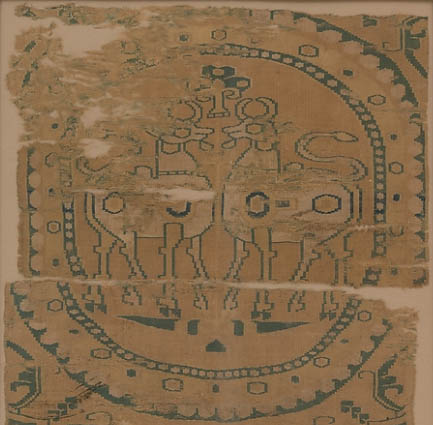

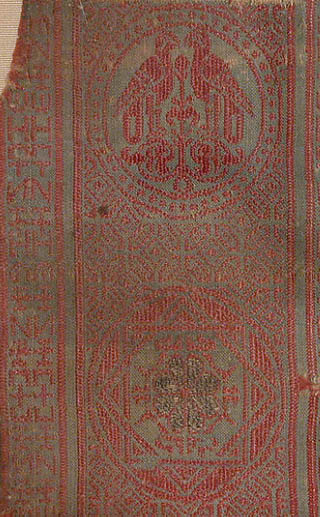

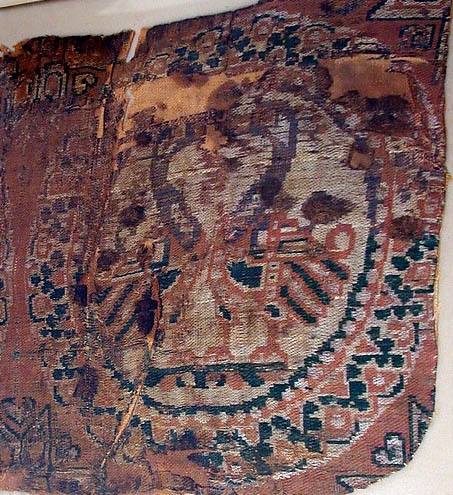

Medallion

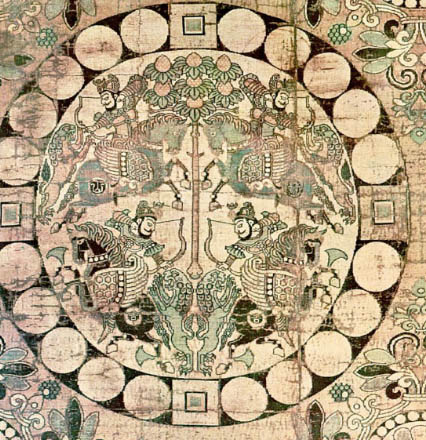

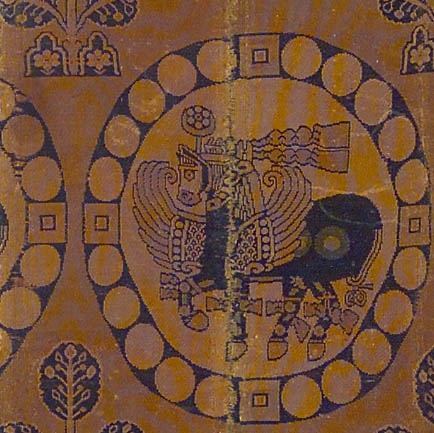

Moving ahead to the next finding we observe that the pattern of the pearl circular border (Medallion) with the top/bottom/and sides concentric squares, circle or crescent is another Sassanid motif and an offshoot of Sassanid artworks. Traced evidences show that many designs consists of the roundel has appeared in Islamic World, India and China.

Figure 6. A. Fragment, eighth century CE. Attributed to Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1938)38.147; B. Textile with Pearl Roundels with Dragons, ninth century CE. Central Asia, China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1998)98.147; C. Textile with Horned Animals in a Pearl Roundel, seventh century CE. China (Xinjiang, Central Asia). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1996)96.1a,b; D. Nose ring, twentieth century CE. Gujarat, India. Victoria and Albert Museum IS.317-2019.

Figure 7. A. Roundel with Candelabra Tree, seventh-ninth century CE. Attributed to Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1917)17.22.1; B. Bowl emulating Chinese stoneware, ninth century CE. Iraq, probably Basra. Islamic. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1963)63.159.4; C. Fragment, thriteeth century CE. Attributed to Spain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1987)87.440.2.

Figure 8. A. Textile Medallion, sixth century CE. Sassanid, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1890)90.5.10; B. Textile fragment with Roundel and Bird, ninth century CE. Country of Origin Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (2015)2015.796.5; C. Roundel, sixth century CE. Attributed to Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1965)65.24.1; D. Tile with ducks from the courtyard of the Buddhist monastery at Harwan, fifth century CE. Gupta Period, Harwan, India. Ashmolean Museum. EAX.2043.

Bird motif holding a string

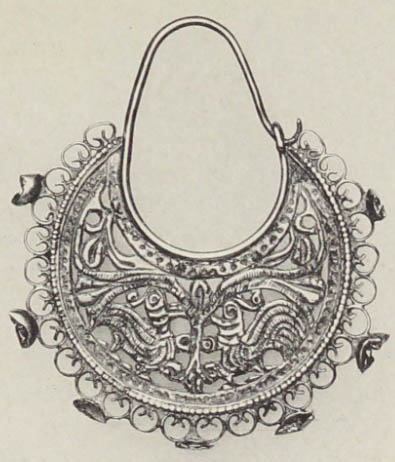

The trace of the third footprint is that of a bird motif holding a string of pearls or a tiny branch of flowers in its beak; the same is the case of the motif of a bird carrying a tiny straw in its beak flying to make a nest or carrying the fodder for its tiny ones. This has its origins in the Sassanid design. It was later modified as a motif of a bird holding a string of pearls, a three beads pendant in the middle (which is quite similar to the necklace worn by the Sassanid kings) in the early Sassanid product design. Also, in another case, a goose holding a jeweled ribbon in the beak on Sassanid textile can be considered as an inspiration from the former design. This pattern is another Sassanid motif and this form was a common decorative pattern seen on Sassanid gold and silver wares, that could have probably been emulated by Islamic, Indian and Chinese designers [9].

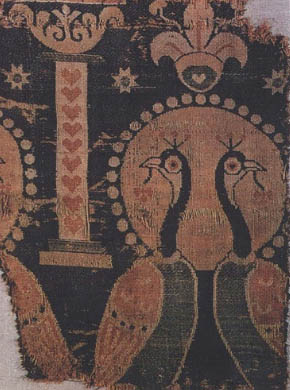

Figure 9. A. Textile with Confronted Birds on Flower, early eighth century CE. China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1996)1996.103.2; B. Bowl with Two Facing Peacocks, tenth century CE. Iraq, probably Basra. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1964)64.134; C. Textile fragment with ducks in roundels, eighth-ninth century CE. Central Asia; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1999)99.325.229; D. Textile fragment with birds, palm tree, and stylized plants, tenth- fifteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. Ashmolean Museum, EA1990.167.

Figure 10. A. Fragment of an imported Chinese ewer, ninth century CE. China. Changsha; excavated in Iran, Nishapur. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1938)40.170.455a,b; B. Wall decoration with birds and vegetal design, sixth century CE. Sassanid. Ctesiphon; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1932)32.150.20; C. Appliqué Plaque with a Tree and Four Birds, twelfth century CE. Attributed to Iran or Iraq. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1949)49.71.1; D. Textile fragment with facing birds in medallions, nineteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. Victoria and Albert Museum, IS.541-1952.

Birds standing in a symmetrical position

In Sassanid product design, using bird forms were very popular; and the design of the ‘birds standing in a symmetrical position face to face’ was used during the Sassanid period. This pattern were commonly used to decorate the iwans and reception halls of elite Sassanid houses, showcasing the popularity of this Sassanid motif. The same can also be tracked in Indian, Chinese and Islamic design, which were obviously marks of Sassanid footprint.

Fluttering ribbons

Fluttering ribbons around the neck can be the next footprint which appeared in the Sassanid art first in the 3rd century. Later the same footprint appeared everywhere in Sassanid territory, then again it went further to West and East [10].

Figure 11. A. Drachm of Bahram IV, 388-399 CE. Sassanid, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1898)99.35.2965; B. Textile fragment: walking ram with a neckband and fluttering ribbons, seventh century CE. Sassanid, Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1977)77.232; C. Dancing Nataraja in medallion, India; D. Textile with animal pattern, twentieth century CE. Gujarat, India.

Crescent

In another case, it is pertinent to mention the use of the crescent shape in Islamic art and the idea of adding colour to the four sides of the bowl edge in Changsha wares which are Sassanid footprints with the possibility of deriving an inspiration from Sassanid motif of ‘Crescent & Star’ by Muslim and Chinese designers[11]. This is visible in the motif of a bird wearing a pearl-studded crescent on its breast; it is comparable to a royal crown/bottom/and sides depicted on Sassanid coins; this element is common on textiles and potteries of Muslims and Chinese, and these pattern are actually identified by scholars as their products.

Figure 12. A. Drachm of Khosrow II with royal crown/bottom/and sides crescents, 590 CE. Sassanid, Iran. The People Museum. 2017 . 3Iran-521; B. Gold earring, Persian, Seljuk period, eleventh century CE.; C. Sealing, 7th century CE. Sassanid, Qasr-i Abu Nasr, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1936)36.30.157; D. Crescent+star-Shaped Pendant with Confronted Birds, eleventh century CE. Made in Egypt, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1915)30.95.37.

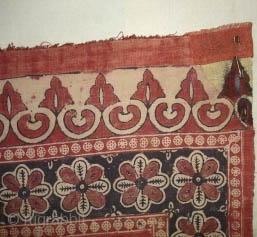

Palmettes / pikes

Palmettes decoration through pikes (Spades) and heart shaped leaves is another important motif shows footprint of Sassanid culture commonly used to decorate the products and interior decoration of elite Sassanid houses. Researchers believe that the date palm and palmettes pattern are components of the Sassanid motif [12]; which has its roots in Achaemenid and Elamite. One can see its effect on the West and East.

Figure 13. A. Cup with Floral and palmettes Decoration, second half twelfth-thirteenth century CE. Attributed to Iran, probably Ray; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970 (70.36); B. Wall decoration with palmettes and geometric design, sixth century CE. Ctesiphon. Sassanid. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (1932)32.150.32; C. Prayer Arch Kalimkari, nineteenth Century CE. Kutch, Gujarat, India. Khadi Cotton cloth; D. Silk fragment with peacocks on pearl roundels, sixth century CE. Sassanid, Iran. The Treasury of Aachen Cathedral.

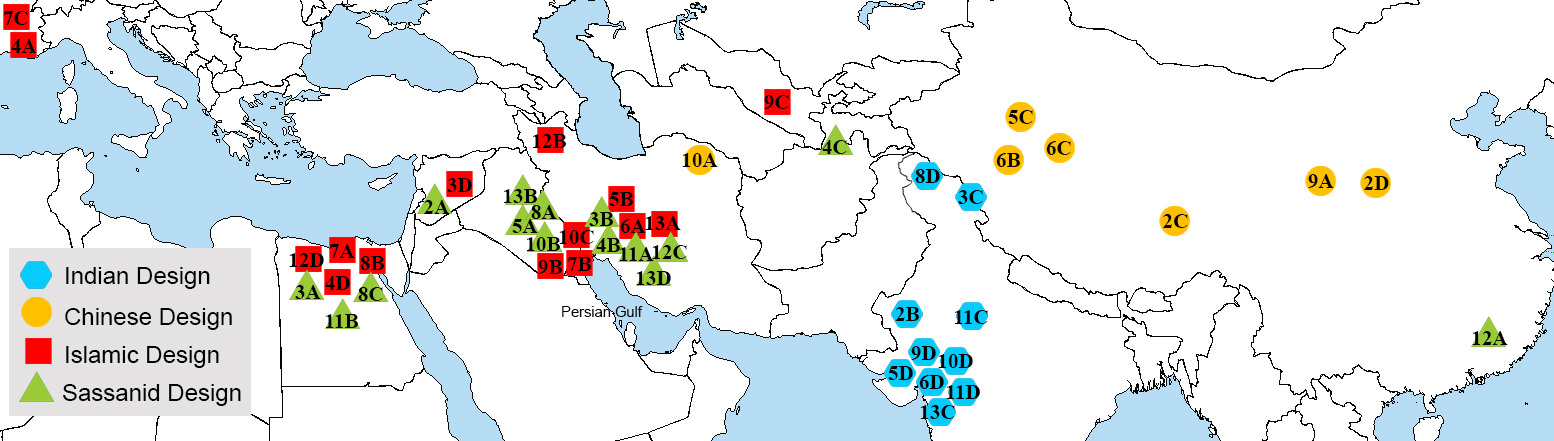

Figure 14. Sassanid footprints (Figs 2-13).

Table 1. Instances of excavated products for each pattern.

|

Pattern |

Sassanid |

Islam |

Indian |

Chinese |

|

Hunting Lion |

2.A,3.AB |

3.D, 4.D |

2.B, 3.C |

2.CD |

|

Medallion |

2.A,3.A, 4.B, 5.A, 7.A, 8.AC, 11.A, 12.A, 13.D |

3.D, 4.AD, 5.B, 6.A, 7.BC |

2.B, 5.D, 6.D, 11.C |

2.C, 4.C, 5.C, 6.BC, 9.C |

|

Bird holding a string |

8.A, 8.C, 13.D |

8.B, 9.B |

8.D, 11.D |

5.C, 9.AC |

|

Birds standing in a symmetrical position on the /in front of the Palmettes |

10.B, 13.D |

6.A, 7.C, 9.B, 10.C, 12.BD |

5.D, 6.D, 9,D, 10.D, 11.D |

9.AC, 10.A |

|

Fluttering ribbons |

2.A,3.AB, 8.AC, 11.AB |

|

11.C |

2.C, 4.C, 5.C, 9.C |

|

Crescent |

4.B, 8.A, 12.AC |

7.B, 12.BD |

|

4.C, 5.C |

|

Palmettes / pikes |

4.B, 5.A, 7.A, 10.B, 13.BD |

9.B, 10.C, 13.A |

5.D, 6.D, 9.D, 13.C |

6.C, 9.C, 10.A |

Conclusion

We can conclude all together from the above footprints that these motifs have managed to transcend boundaries and have inspired art mostly attributing to Sassanid trade. In this research, one can observe the evidences that show how Sassanid influenced product design of Indian, Islamic and Chinese design. Sassanid products were exported through the ancient Silk Route to different part of Sassanid territory from Spain to India and China. This also reinforces the fact how these cultures have evolved with artistic transformations and how adaptations were adopted. Then, these precious qualities of luxurious products led to the transfer of Sassanid patterns to product designs which were made centuries after the collapse of Persian Sassanid. The Sassanid culture was a pioneering, innovative and inclusive culture. The brilliant and varied patterns infused and showed aspects such as humanist consciousness, customs and cultural circulation in the history. The exploration and appreciation on forms and implications of these patterns can help us in grasping development tendency and cultural connotation of the traditional decorative patterns better.

References

[1] Taghi Nasr, (1974). The Eternity of Iran. Tehran: The Ministry of Culture and Arts publication.

[2] Nehru, P.188 mentioned in Nasr (1974). PP. 181-183.

[3] Alonso Constenla Cervantes (2013). Sassanid Empire. https://www.ancient.eu/Sassanid_Empire/

[4] Wood, Frances (2004). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[5] Coin, 621 CE. Tang dynasty. Excavated in Siraf, Site: F Area: S Context: 38, Copper alloy coin; Diameter: 25.1 mm. The Trustees of the British Museum. 2009,4088.183.

[6] Godard (1962). L’Art de L’Iran, B. Arthaud, Paris. In Persian translation of ‘The history of Persian civilization’ by Mohii 2002, P. 33.

[7] Oliver Watson, (2015). “CHINESE-IRANIAN RELATIONS : Mutual Influence of Chinese and Persian Ceramics” Encyclopaedia Iranica, Accessed in May 2017. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chinese-iranian-index/

[8] Karel Otavsky, (1998). “Zur Kunsthistorischen Einordnung der Stoffe,” in Idem, ed., Entlang der Seidenstrasse: frühmittelalterliche Kunst zwischen Persien und China in der Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, pp. 119-214.

[9] feng Zhao, and Dongfang Qi (2011). The Western Influence on the Textiles in the Silk Road (the 4th Century – the 8th Century). Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House.

[10] Xiaoxia Zhang, (2016). “Birds on the Fabrics of the Tang Dynasty” Fine Arts & Design, Vol. 167, Issue 5, PP. 85-89.

[11] Mohsen Jaafarnia, Avinash Shende, Sahar Boroomand and He Renke (2020). Magical Spell or Household Ceramic Bowl: Sassanid Crescent on Islam and Changsha Ceramics, Ceramics: Art & Perception (A&HCI journal). ISSN: 1035-1841, Vol.115, Issue 1.

[12] Edward H. Schafer, (1963). The Golden Peaches of Samarqand. Oakland: California University Press.

![]()

© 2021 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).