Mohsen Jaafarnia, Ji Tie, Sahar Boroomand, Avinash Shende, Seyed Hashem Mosaddad and Mohsen Saffar Dezfuli (2021). Ancient trade on the Silk Road: A comparison of Sassanid designs on India, Islam, Han Art. The People Museum Journal , Volume 7, Issue 1, ISSN 2588-6517

Ancient trade on the Silk Road: A comparison of Sassanid designs on India, Islam, Han Art

Mohsen

Jaafarnia

Associate Professor, School of Design, Hunan University, China.

Ji Tie

Professor, School of Design, Hunan University, China.

Sahar Boroomand

School of Art and Architecture, Central South University, Changsha, China.

Avinash Shende

Industrial Design Centre, Indian Institute of technology Bombay, India.

Seyed Hashem

Mosaddad

School Of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science &

Technology, Tehran, Iran.

Mohsen

Saffar Dezfuli

School Of Architecture and Environmental Design, Iran University of Science &

Technology, Tehran, Iran.

This research is funded by “National Key R&D Program of China No. 2019YFB1405702

Introduction

Sassanid design is not a sudden phenomenon in Iranian art, rather the art of this period is a summary of all the eras of Iran. This art during the 524 years of the time when the kings of the dynasty reigned, at the same time as its diversity and multiplicity, has created a manifestation of unity. Hence, a clear coherence and homogeneity can be observed in all the works of this era.[1] Their design has travelled when the Sassanid empire (224-651 CE) was the major power in the Central Asia and Near East for 400 years. Their culture awarded a preponderant importance to the decorative aspect in their design that shows their culture; which they used as resource and vehicle of expression with a deep philosophical meaning about life. This research aims to track their patterns which commonly used in Chinese, Indian and Islamic design by a comparative study on their artworks using production dates to provide a perspective of the influence.

Sassanid extended the authority eastwards into the north-western Indian subcontinent where autonomous Kushans were ruling. later the Kushan empire (30-250 CE) declined to be replaced by the Indian Gupta Empire (320-550 CE) in the 4th century, it is clear that Sassanid remained relevant in India's northwest (Gujarat) throughout this period, even after Sassanid, and entering the Islam, many Persian people immigrated to Gujarat .[2] In another direction, they extended the authority eastwards into the Central Asia. During the Sassanid era, Persian design influence has extended into China and India. [3] Iran sustained relations with Indian and Chinese in ancient times; Indian relation goes back to Achaemenid era (559–330 BCE),[4] and Chinese goes back to Parthian era (247 BCE- 224 CE) .[3] The Sassanid Empire continued the practice of its predecessor the Parthian Empire and maintained active foreign relations with India and China. A Chinese traveller, Huan Tsang, wrote: “all they [the Persians] make the neighbouring countries value very much [through making connections]” . [3]

This article illustrates effect of Sassanid design along the Silk Road product design in India and China. That time goods, including textiles; silver, gold wares; glass; brocades, carpets and rugs; skin, leather; pearls and other items, with Sassanid design were carried by merchants everywhere on the Silk Road .[5] The Chinese were interested in Persian art. On several occasions, Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians to the Chinese imperial court.[6] Edward H. Schafer, in commenting on this practice, wrote: “The Chinese taste for the exotic permeated every social class and every part of daily life: Persian figures and decorations appeared on every kind of household objects.” .[7] In opposite side Persians import goods from China (paper, silk and ceramic wares) and India (spices, ivory, precious stones and gems). Because of being in the central location, the Kushan Empire became a wealthy trading hub between the people of India, and Han (China), and people of Persia. Indian spices and Chinese silk changed hands in the Kushan Empire, turning a nice profit for the Kushan middle-men .[8] Good roads and bridges, well patrolled, enabled merchant caravans to link Ctesiphon with all important cities on the Silk Road in India and China; and harbours were built in the Persian Gulf to quicken trade with India and China. Land and maritime trade were important for them (Persian, Indian and Chinese). Sassanid merchants ranged far and wide trade on the lucrative Indian Ocean trade routes. They benefited from the Silk Road trade and shared a common interest in preserving and protecting trade. A large number of Sassanid coins from different kings have been found in southern China (Shanghai Museum), and India (The British Museum); and early Tang coins were excavated by David Whitehouse in Siraf in southern Iran (British Museum; Fig. 19.D) confirm Sassanid maritime trade. This trade gave opportunity to Chinese and Indian designers to adopt and adapt Sassanid designs. This is seen in a few exotic products industries.[9& 10] Sino-Persian and Indo-Persian artwork exchanges were a distinctive feature of their bilateral relations (Fig.1AB).

After Islam entered Persia and the collapse of the Sassanid Empire, one group of Persians landed in what is now Gujarat, where they were allowed greater freedom to observe their old customs and to preserve their faith. In the same time in Persia, Muslims artists developed their art using Sassanid motifs in Islamic art. This happened as Muslim artists developed intricate geometric patterns, elegant calligraphy, and artistically-stylized writing.[3 & 11]

Design of a product namely form and its constituent of elements are manipulated by the designer in order to satisfy the user; due to the subjective nature of the visual quality, it is often difficult for a researcher to compare the constituents of two different designs that share similar visual characteristics. This difficulty gets magnified when manufacturers from a different nationality and culture try and introduce products to another culture. Over time, changes in lifestyle and culture have changed the product form which bore influences on its design. This visual study could create a significant knowledge base for designers engaged in design of products for different culture.

In product design comparative studies with respect to form preferences offers diverse challenges. In this article we have used a comparison methodology involving evidences and substantiation data. The data assimilated is based on a widespread historical research of past cultural and commercial relation between Iran, India and China. Here the comparative design study is a design research that seeks to find relationships between independent and dependent design variables, has occurred in the past between these three cultures by comparing groups of product design samples. There are similarities and differences between samples of this comparative research. This entry discusses these differences, as well as similarities, to explore these types of designs. Comparative research is a way to broaden our thinking about product design. This type of research is particularly useful when trying to identify cultural relation; ones that are not likely to be documented anywhere but in products themselves.

Figure 1. A. Persian bowl with Chinese dragon motif, fifteenth century CE. Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; B. Persian bowl with Indian elephant motifs. Iran, Kashan. Bowl; 14th Century, Ilkhanid period.

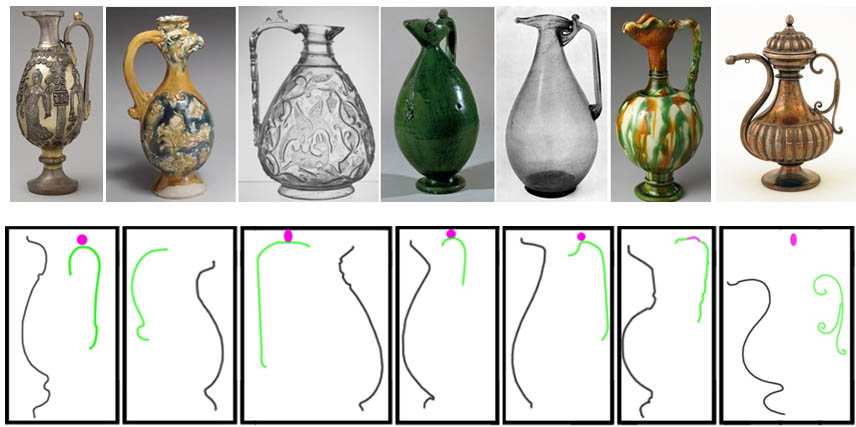

Pear-shaped jugs

Conical jugs which have a pear-shaped body, handles, a long cylindrical neck with thumb-rests attached, in which the main body expands at the bottom have a long history in Sassanid art. (Figs. 2A and 3A). This design appears later in Chinese design (Figs. 2BCDEF) and Indian art (Fig. 2G). It evolved in China during the late seventh century of the Tang dynasty, when Sancai funerary wares were popular (Fig. 2F).[12] In India the same shape vessel used probably for rosewater of funeral ceremony. It has a pear-shaped body decorated with lobed forms. The handle is made up of strips of metal and the domed and gadrooned lid has a pointed finial. The spout is attached to the base and is elegantly curved to echo the overall shape of the pear (Fig. 2G). In another case it appears on (Fig. 2B) a Tang Dynasty flattened, pear-shaped, vessel with a blind spot in the shape of a phoenix head joined to the bird’s head with an arched handle to the upper portion of the body is another example. The solid foot is high and splayed. Two low-relief panels ornament the sides. One shows a phoenix standing on a lotus blossom in Mithra’s pose of standing on a lotus flower in the rock relief of the crowning ceremony and investiture of Ardashir II (Taq Bostan, Sassanid). The other side shows a horse-riding hunter, with bows and arrows, turning back in the classic “Shapure II, Sassanid King” pose. Standard Tang Sancai glaze covers the vessel. It is also seen in Islamic design (Fig. 2C), this is an example of a pear-shaped glass jug, discovered in Egypt. It has a typical geometric, animal, and floral Sassanid decorative patterns on the surface. These instances of similar design can be compared to ewers discovered in Persia, and a comparison shows that the ewer shape derives from Sassanid metalwork which illustrates the impact of trade along the Silk Road. [13 &14]

Figure 2. A. Sassanid ewer, sixth-seventh century CE. Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; B. Phoenix-headed ewer, seventh–first half of the eighth century CE. Tang Dynasty. China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; C. Rock crystal ewer, eleventh century CE. Egypt. Victoria and Albert Museum; D. Jug, seventh - tenth century CE. Tang Dynasty. China. Collection Calmann; E. Eastern glass Jug, eighth century CE. Tang Dynasty. Shoso-in, Nara, The Imperial Household Agency; F. Ewer, late seventh century CE. Tang dynasty. China, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; G. Lobed vessel, ninetieth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 3. A. Sassanid ewer, Early seventh century CE. Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; B. Changsha ware, ninth century CE. Tang Dynasty. China. Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House; C, D, and E. Changsha Wares, Late ninth century CE. Tang Dynasty. China. Private Collection of Mr. Lin an, Changsha.

Figure 4. A. Sassanid lobed gold bowl, fifth-sixth century CE. The State Hermitage Museum; B. Lobed Changsha ware. Late ninth century CE. China. Tang Dynasty. Hunan Provincial Museum, Changsha; C. Cup with Figures in a Landscape, ninth century CE. China. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; D. Lobed silver pedestal bowl, nineteenth century CE. India, Invaluable Collection; E. Lobed bowl, sixteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Ashmolean Museum.; F. Bowl, 17th century CE. Mughal period, India. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

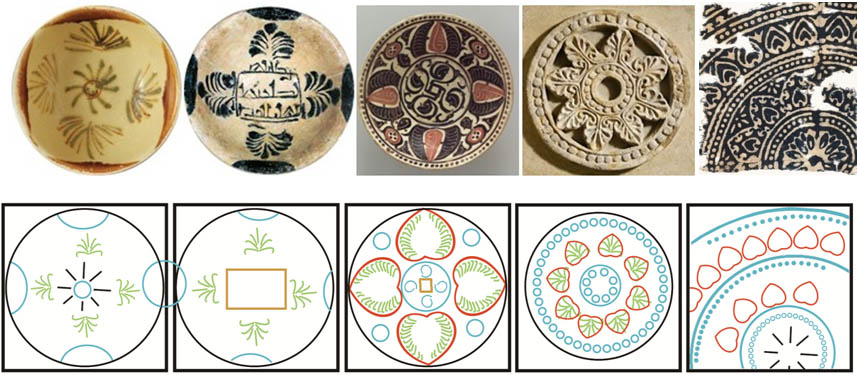

Lobed forms

The use of lobed forms in design ware began during the Parthian era. In the Sassanid era, it reached its highest level. The lobed form represents a mountain range. It was used in two ways: first in a surface pattern featuring a mountain range (Fig. 3A), provides an example with its overall composition and motifs showing a transition from a figural style to a rhythmic repeating pattern. The second is a lobed edge design around bowl rims (Fig. 4 A). Later, lobed vessel design reached India and China (Figs. 2G; 3BCDE; and 4BCDE). This is further evidence of a design traveling along the Silk Road trade.[3, 15, 16, & 17]

Figure 5. A. Changsha ware with heart-shaped leaves. ninth century CE. Tang Dynasty. Belitung shipwreck. Asian Civilisations Museum. B. Artwork with palm leaves, ninth century CE. Abbasid Dynasty, Iraq. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art; C. Ware with palm leaves, tenth - eleventh century CE, Abbasid Dynasty. Nishapur, Iran. National Museum of Iran; D. Sassanid wall panel with a guinea fowl, sixth century CE. Ctesiphon. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; E. Sassanid wall panel with wings and a Pahlavi device encircled by pearls, sixth century CE. Ctesiphon. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; F. Textile fragment with palm leaves, tenth- fifteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Ashmolean Museum.

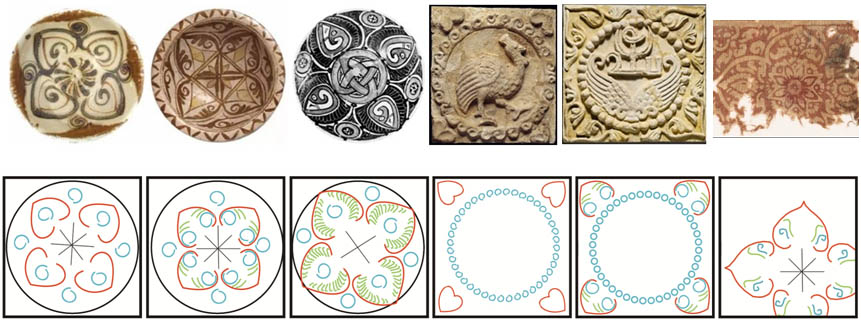

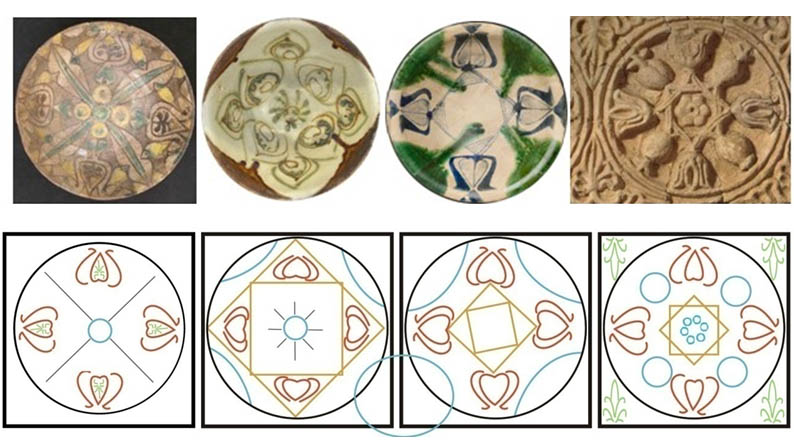

Palmettes piercing pikes and heart-shaped leaves

Heart-shape Palmettes are another Sassanid art motif commonly used in interior decoration of elite Sassanid houses and on house wares. Many examples have been found in houses excavated near Ctesiphon. The popularity of this pattern is seen in figures 5DE; 6D; and 7D. One instance is of a roundel (Fig. 6D) decorating that consists of radiating palmettes. This was a design source for generating many Islamic, Indian and Chinese patterns. This motif suggests relations between Sassanid culture and Indian and Chinese cultures via the Maritime Ceramic Route.[18]

Figure 6. A. Changsha Ware, ninth century CE. Tang Dynasty. Belitung shipwreck. Asian Civilisations Museum; B. Islamic ware with palm leaves, ninth century CE. Abbasid Dynasty. Most likely made at Basra in Iraq. Tareq Rajab Museum, Kuwait; C. Bowl with Red and Purplish-black Palmettes, tenth- eleventh century CE. Attributed to Nishapur, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; D. Sassanid roundel with radiating palmettes, sixth century CE. Ctesiphon. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; E. Textile fragment with medallion and palm leaves, tenth- fifteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Ashmolean Museum.

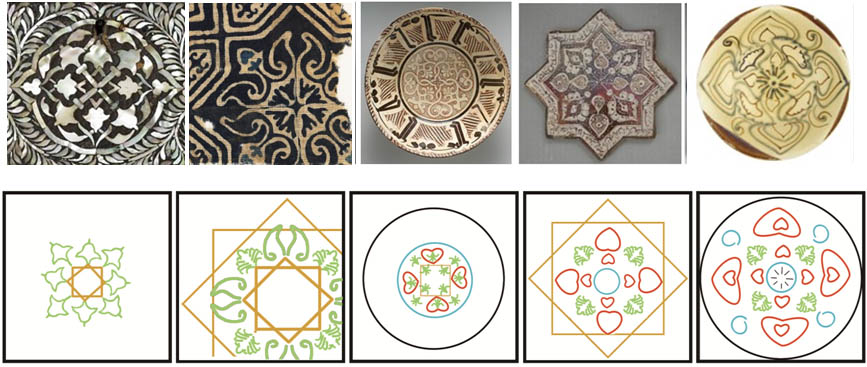

Geometric pattern

Sassanid designers exploited geometric patterns in their artworks. Sassanid geometric designs, frequently show squares and circles. These shapes are meaningful in art of Islam, India and China. These associations represent why Sassanid geometric patterns became so popular in these cultures. The geometric pattern of Changsha ceramics, commonly show squares and circles. Regina Krah, et al., in their book writes: “In the context of the … [Belitung shipwreck] cargo, this design is a signature motif, appearing most frequently ...shows relationship between [Sassanid artwork] and Chinese ceramics during this period”. This is proven by the similarities of these figures.[19]

Figure 7. A. Bowl, ninth century CE. Attributed to Nishapur, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; B. Changsha ware. ninth century CE. Tang Dynasty. Belitung shipwreck. Asian Civilisations Museum; C. Bowl with pikes, Early ninth century CE. Abbasid Dynasty. Ashmolean Museum; D. Sassanid geometric pattern, sixth century CE. Ctesiphon. [20]

Figure 8. A. Casket with geometric decoration, sixteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Ashmolean Museum; B. Textile, tenth- fifteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Ashmolean Museum; C. Bowl with radiating pikes and palm leaves, late tenth-eleventh century CE. Made in present-day Uzbekistan, probably Samarqand. Excavated in Nishapur, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; D. Star-shaped tile, 1265 CE. Kashan, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; E. Changsha ware with heart shaped leaves. ninth century CE. Tang Dynasty. Belitung shipwrecked. Asian Civilisations Museum.

Fig. 8A Casket with geometric decoration, sixteenth century CE. Gujarat, India. The Ashmolean Museum.

Conclusions

Taking this evidence together, we conclude that Chinese, Indian, and Muslim designs ultimately derived these Sassanid motifs. The evidence is that most of these motifs appeared first in Sassanid product design. The influence on Indian, Islamic and Chinese product design occurred along the Silk Road shows where Sassanid products had been exported to. The products led to the transfer of Sassanid patterns in the decades after the collapse of the Sassanid Empire. One can compare the blue circle, red heart-shaped leaves, yellow square, black line and green palmettes from Sassanid in Chinese, Indian, and Islamic designs. The Sassanid culture was a pioneering, innovative, and inclusive culture. The brilliantly-colored and varied patterns infused aspects of a humanist consciousness, customs, and cultural circulation. The exploration and appreciation on product designs and implications of these patterns can help to better understand development tendencies and cultural connotations of the traditional decorative patterns. The contribution of Persian, Indian and Chinese designers to this wide range of art, design, and commerce disciplines is often overlooked. It is hoped that this paper provides a glimpse of the rich cultural heritage within, and between, these three regions, where have played a role in advancing product design. This overview of the history shows frequent exchanges which are the distinctive features of their bilateral relations.

References

[1] Ghirshman. R. Persian art, Parthian and Sassanian dynasties, 249 B.C.-A.D. 651 (The Arts of mankind), Bremen: Golden Press, 1962, pp. 211-212.

[2] Crystal, E. “Sassanid Empire”, Crystalinks, 2019, https://www.crystalinks.com/Sassanid_Empire.html (accessed on February 2, 2021).

[3] Nasr, T. The Eternity of Iran from the Viewpoint of Western Orientalists, Tehran: The Ministry of Culture and Arts publication, 1974, pp.177–184.

[4] Dadvar, A. and Mansouri, E. An Introduction to the Myths and Symbols of Iran and India in Ancient Times, Tehran: Alzahra University and Kalhor Press, 2006, pp. 266–270.

[5] Qi, D. Research on Gold and Silver Wares of the Tang Dynasty, Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 1999, p. 277.

[6] Wood, F. The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, pp. 55.

[7] Schafer, E. H. The Golden Peaches of Samarqand, Oakland: California University Press, 1963, pp. 42-43.

[8] Constenla Cervantes, A. “Sasanian Empire” 2013, https://www.ancient.eu/Sasanian_Empire/

[9] Godard, A. L’Art de L’Iran, B. Arthaud, Paris, 1962, In Persian translation of ‘The history of Persian civilization’ by Mohii 2002, P. 33.

[10] Mohii, J. The history of Persian civilization, Tehran: Gutenberg Publication, [in Persian] 2002, pp. 33.

[11] Blair, S.S. Islamic Calligraphy, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008, pp. 33.

[12] Durant, W. The Story of Civilization. Vol. 1: Our Oriental Heritage, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976, pp. 64-65.

[13] Azari, A. History of Relation of Iran and China, Tehran: Amir Kabir Publication, [in Persian] 1988, pp. 133.

[14] Maser, E. A., Carswell, J., and Mudge, J. M. Blue and White: Chinese Porcelain and Its Impact on the Western World, Chicago: University of Chicago; and David & Alfred Smart Museum, 1985, pp. 84-85.

[15] Abaei, M., and Jaafarnia, M. “Where Was the Destination of Black Stone Shipwreck: Comparative study on founded products in Iran and products of Black Stone”, presented at the New Silk Road Program 2015, Hunan University, Changsha, (July 2015).

[16] Von Ferscht, A. “Meta-Museum: Chinese Export Sliver – The Nineteenth Century Phenomenon Equivalent to the IPAD”, Chinese Export Sliver, 2014, http://chinese-export-silver.com (accessed on May 25, 2017).

[17]Kaikodo “Lobed Elliptical Parcel-Gilt Silver Cup”, Kaikodo, Asian Art, 2015, http://www.kaikodo.com/index.php/exhibition/detail/the_immortal_past/506 (accessed on May 25, 2017).

[18] Laufer, B. Sino-Iranica: Chinese Contributions to the History of Civilization in Ancient Iran, Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1919, pp. 74.

[19] Krahl, R., Guy, J., Wilson, K., and Raby, J. Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds, Singapore: Smithsonian Books, 2011, pp. 98.

[20] Arthur Upham Pope, and Ackerman, P. Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Time to the Present, North Clarendon: Charles E Tuttle Co., 1981, pp. 177.

![]()

© 2021 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).