Majid Rahmandoost and He Renke (2023). The Legacy of Longstanding Sino-Persian Friendship in the Study of Artistic Cultural Interaction. The People Museum Journal , Volume 9, Issue 1, ISSN 2588-6517

The Legacy of Longstanding Sino-Persian Friendship in the Study of Artistic Cultural Interaction

Majid Rahmandoost

PhD scholar, School of Design, Hunan University, China.

He Renke

Professor, School of Design, Hunan University, China.

Abstract

Iran and China have had long-standing and extensive relations throughout history as two great and ancient civilizations, one in East Asia and the other in West Asia. Before Islam, these two countries were only connected by land through the famous Silk Road, and after Islam by sea. These commercial contacts and exchanges between the two countries have had an impact on their arts. An overview of the historical relations between China and Iran displays that recurrent interactions of trade, religion, culture, art, science, and technology are the classifiable features of their mutual relations. Here we have outlined the historical perspective that influenced the development of the aesthetics of products in both Persian and Chinese culture. We have comprehended that the products were exported to China During Sassanid and later the Changsha wares, northern and southern wares with same design of Sasanian Design were exported to Iran in the Abbasid Dynasty. (Jaafarnia, 2015) Most of the previous studies have examined the impact of Chinese art on Iran and the influence of Iranian art on China has not been much considered. In this study, we investigate the effect of Iranian art on Chinese art, especially the effect of using Iranian form, technique, and ornament on Chinese products. According to the results of the research, it can be said that Iranian art has also had a significant impact on Chinese art and culture.

Keywords: Product Design, Ceramic, Changsha, Tang Dynasty, China, Persia.

Introduction

China-Iran relations date back to over many centuries. Since ancient times, the Parthians and Sassanids had various communications with China, and the two lands were further connected via the Silk Road. The Chinese explorer Zhang Qian, who visited the western neighboring countries of the Han Dynasty in 126 B.C., made the first known Chinese report on Parthia. In hisportrays, Parthia is named “Ānxī” (安息), a transliteration of “Arsacid”. Under the description of Zhang Qian, commercial relations between China, and Parthia flourished, as many Chinese missions were sent via the Silk Road throughout the 1st century B.C. (Feng, 1996). The Parthians were very determined to maintain good relations with China and also sent their embassies, starting around 110 B.C. The Sassanid Empire maintained active foreign relations with China Like their predecessors the Parthians, and ambassadors from Persia frequently traveled to China. Commercially, Both land and maritime trade with China was important. A large number of Sassanid coins have been found in southern China, proving maritime trade. On various occasions, Sassanid kings sent their most talented Persian musicians and dancers to the Chinese imperial court (Wood, 2004). Both empires cooperated in guarding the trade routes through central Asia and built outposts in border areas to keep caravans safe. During the Tang Dynasty, communities of Persian-speaking merchants, known as Húrén(胡人), formed in northwestern China’s major trade centers. One of the most famous settlers from Persia was al-Sayyid Shams al-Din Umar. His most famous descendant was Zheng He, who became the Ming dynasty’s most famous explorer and visited Iran several times. Shah Abbas the Great had hundreds of Chinese artisans in his capital Esfahan and Safavid Iranian art was also influenced by Chinese art. In an overview of the history of the interactions, we find that numerous exchanges of culture, religion, trade, art, science, and technology are the distinctive features of their bilateral relations. China and Iran shaped their perceptions and power projection through cultural exchanges and thus, paved the road for their cooperation and friendship (Garver, 2007).In the course of art history, it can be seen that the art of a period or ethnic group is influenced by other tribes or eras of the past. It is obvious that different ethnic groups can influence each other's culture or art. These relationships can also be useful and, while having a positive impact on the culture, create a new form by new expression to the destination art. In the field of pottery, it can also be said that these two great and ancient civilizations have had bilateral Relations. Sometimes one has started and the other has perfected a technique in pottery, and sometimes form, method, or ornamentation has been exchanged. This paper seeks to investigate the similarities in form, patterns, and roots of some techniques in Chinese and Persian pottery to answer this question:

1. Was the origin of the form of ceramic utensils produced during the Tang dynasty in China the Sassanid art in Iran?

CHINA-IRAN Relations

The relationship between China and Iran is very old. The importance of these relationships is so great that there is mythical evidence for it. In the mythological history of Iran, it is said that Fereydoun king of Iran entrusted the land of Tibet, China, and the lands of the East to one of his three sons, Tur or Touj. Thus the land of China originally belonged to the Iranians. (Azari, 1988:13).

According to the sources, the first connection between the two great civilizations of China and Iran was during the Parthian period in Iran. In the reign of Mithridates II(67-124 A.D.), at the same time as the Han dynasty in China, the Great Shahriar of the Parthian Republic founded good relations between China and Iran. the first Chinese ambassador with a delegation of 100 people was sent to the land of Parthia and on the other side The Iranian government decided to send an ambassador to China. The name or some other information about this ambassador and his delegation is unknown to us. two countries’ official relations may be started from this point and continuously become stronger.

The Influence of China–Iran Relations

Due to attacks and the destruction of documents, there are not many documents left in Persian from how and details of the ancient relations between China and Iran, but there are some writings in Chinese, among which are documents that clearly state that the technique of glazing on ceramics has gone from Iran to China. In the second century B.C., during the reign of Parthia, leaded glazes were first found in China. Many historiographers believe that the glaze knowledge was transmitted from Parthians in Persia to Han emperors in China through commercial contacts. The effect of Parthian art on Chinese pottery was not only glazing. Countless Chinese pottery objects show horses, horsemen, and hunting scenes, all made in the style of Persians. Primeval Chinese stories also confirm that the leaded glaze was carried to China by an Iranian merchant. There is also other evidence to confirm that the Iranians sold the prepared glaze paste, which shows why the glaze industry was abandoned from Chinese pottery after the fall of the Han Empire in 220 A.D.(Wolf, 1993:126-127).

Records of art from this period of history in China confirm the strong influence of Iranian art on China. The presence of a sculpture of a lion in one of the sepulchers shed light on the widespread connection between Parthian and China. The Lion did not live in China at all, and there is no remark about the lion in the texts of the Han Dynasty, also Chinese had never seen that before this period. Therefore, in this connection, the lion was the best gift sent by the Parthian king to the Han dynasty (89-106 BC). This animal is so much appreciated by courtiers that artists are encouraged to make a statue of it. It is from this time onwards that artists impart the role of the lion in paintings, textiles, pottery, and other works of art (Daneshpour Parvar, 1994:46). Application of the lion in forms of large-scale sculptures shows the effect of Achaemenid Iran (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Han Dynasty temple sculpture

Source:iranicaonline.org/articles/chinese-iranian-xiv23prettyPhoto

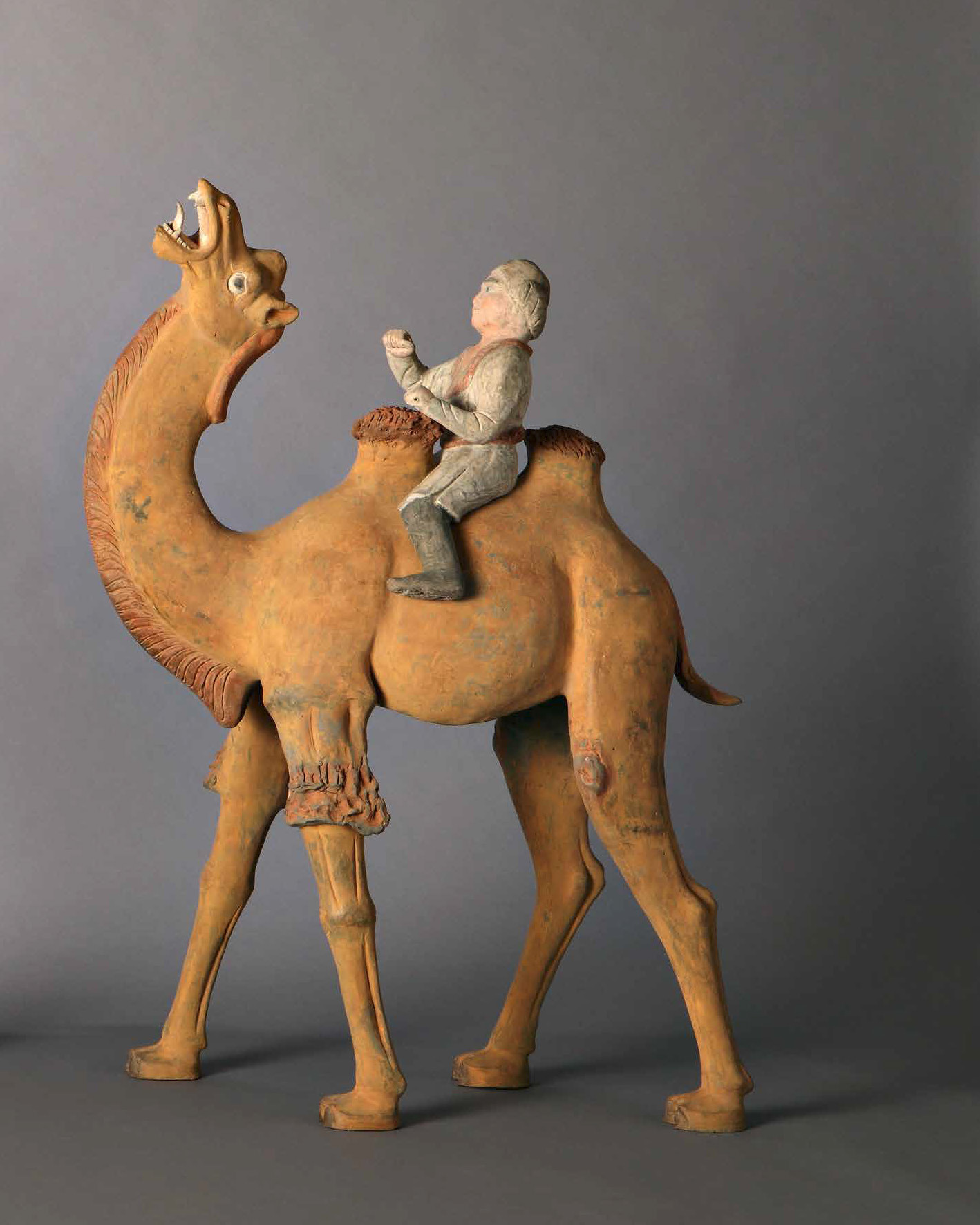

The most flourishing connection between China and Iran was in the Sasanian Empire. In the Sassanid period (224-951 CE) relations between China and Iran were further developed and more cordial relations were established. The movement of Chinese ambassadors and political representatives, as well as tourists and Buddhist pilgrims of China to Iran and neighboring countries is increasing (Azari 1988:34). Meanwhile, the growing tendency of European countries for Chinese goods, especially silk, has led to the growth of traffic in this commercial route, and the Sassanids to take advantage of this lucrative situation, planning and measures It was designed to enhance security and expand this path. These movements also had significant cultural influences that influenced the art of this period in both countries. The details of the face and style of the clay sculptures of this period are well represented by the social life and influence of foreign cultures in China. During the Tang Dynasty in China, besides traditional Chinese sculptures in their graves, they put some pottery sculptures. most of them are not Chinese in terms of shape, form, and type of clothing, and decorated with the famous Tang Tricolor method. The form of clothes and faces is similar to the look and clothes of Iranian people (DaneshpourParvar, 1994:46Figure 2)

Figure 2. The statue of Iranian costumes and forms

Source: Mahler, 1959

From Metalwares to ceramic utensils

the Sassanid Kingdom and the Northern Chinese Dynasty (386-532 CE) had close relations and Iranian metal containers were introduced to China by merchants during this period. A group of gold, bronze, and silver-gold luxury vases, all of which are Figurate in Persian-Greek decorations, have been found in Datong and probably imported from Iran (Iranica 2005) One ofThe important influences of the Sassanid period on Chinese pottery art during the Tang Dynasty is related to silver dishes. An astonishing silver ewer with Iranian gold plated with an embossed fringe of figures taken from Greek mythology was found in a grave from the middle of the 6th century in Ningxia Province (i.e. 2005Figure 3)

Figure 3. Sassanid design ewer

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Chinese pottery artists, after seeing these Metal ewers, made changes in them and produced potteries. Samples of the original Iranian silver Sassanid ewer were imported to China where they were imitated and used in pottery and ceramics during the Tang and Song dynasties (Froom, 2008:66).The form of these ewers is like a bird head with a long neck, decorated with sprayed glaze and colorful glaze common in the Tang and Song periods. The bodies of these pottery have outstanding ornamental motifs that have been made by mold. Even the motifs on these utensils are inspired by the Sasanian arts. Motifs such as the scene of the king's hunting and the legendary birds were common in Iran for centuries (Lotfi et. all, 2015Figure4). But the use of animal shapes in containers in the myths of this was a relic of a prehistoric method. based on the belief that drinking from dishes that are like one of the powerful animals transmitted the power of that animal to the human He does it (Poop and others, 2008: 83)

Figure 4. Bird head ewer, tang dynasty, China late 7th or early 8th AD

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

After the arrival of the early pattern of ewer from Iran to China and Modeling by Chinese potters, these Chinese clay ewers along with other Chinese pottery were imported to Iran. Thus, the initial forms of Iranian metalworking entered Iranian pottery after being exported to China and re-imported into Iran, and potters used forms similar to birds and animals. One of the most obvious of these imitations is from the Seljuk period, of which many examples remain (Figure5).

Figure 5. bird head ewer, Kashan, Iran, 7th century

Source: kambakhshfard, 2012: 202

According to the evidence, one of the reasons for the prevalence of these dishes is that Islam has entered Iran. According to Islamic law, eating and drinking in containers made of gold and silver was forbidden, which led to a significant reduction in the boom in metalworking. However Iranian artists used their ingenuity to create the same forms with other materials such as pottery. (Lotfi, et. All: 2015) They also responded to the luxury of the court through their invention in the production of golden glaze. The charm of this glaze was that without using even a small amount of gold, after baking, the ceramic looks metallic and golden. This characteristic made pottery a suitable substitute for gold and silver dishes in Islam due to observing religious standards and prohibiting the use of gold and silver dishes in Islam (Nikkhah, 2010: 110).

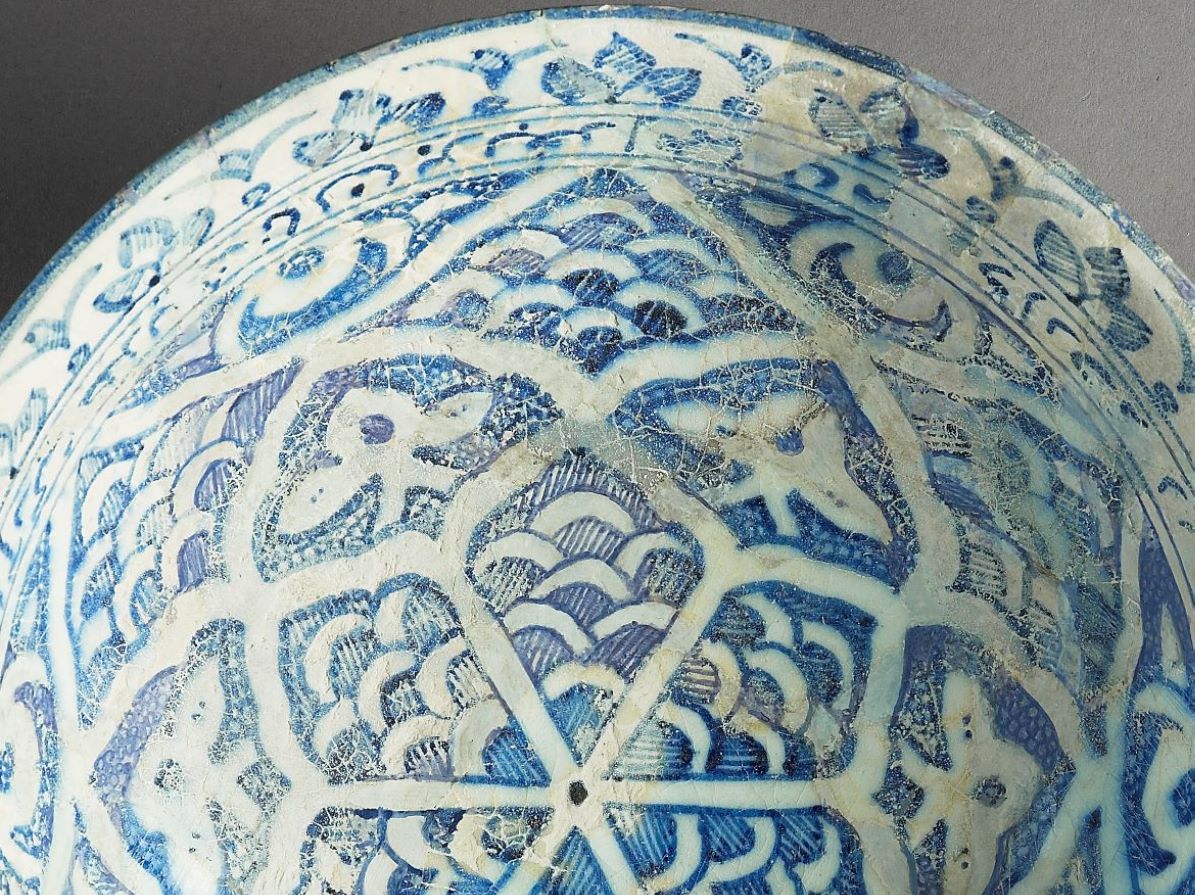

Blue and white ceramics

the origin of the white and blue dishes was Iran. However, the use of blue in Iranian glaze is due to the evolution of the glazing technique. Although cobalt was abundant in Iran, it was not used in early Iranian pottery. At least until the end of the 5th century, the use of blue color in Iranian pottery did not become widespread and this was due to a change in the method of application and not the sudden interest in the blue color that was most commonly used in graffiti painting. The change that made it possible to make blue was that alkaline glaze replaced the lead glaze, which turned copper oxide into brilliant "turquoises" instead of the green used in early pottery. Now cobalt was also used in glazes that gave dark blue (Wilkinson, 2000:141).

Initially, the clay bodies were covered with white mud and then decorated with blue and black. But in the 5th century, a very important change took place, and that is the acquaintance of the potter artist with a kind of Chinese soil that was common in the Song period in China (960-1279 CE) and exported to the Middle East (Karimi and Kiani, 1985: 35).

new pottery that was completely white and made with more delicate and thinner was popular. Unfortunately, Iranian potters at the time were unable to control the blue decorations of cobalt underglaze. It was the Seljuk sprinkled cobalt blue, which motivated Chinese potters to apply blue cobalt to ceramics until the end of the Mongol (1260-1368)during the Yung period. (Fehervari, 2000: 236)

The Chinese imported cobalt from Iranian mines by sea route to decorate their ceramics. One of the major imports brought to China was the cobalt stone, which the Chinese called the “Mohammadi blue” because it was imported from a Muslim country (Gerald, 1988:680).

But the most common use was after Islam, which is known as a sub-glazing ornament. underglaze ornamentation on pottery has been common in the centers of pottery in the north and northeast of Iran from the early years of Islam. Figures and ornamentation of the underglaze were often done in blue and black, but sometimes turquoise, azure, and dark green colors were added to it. The most common decoration is the style of underglazed dishes painted in blue on a white background (Karimi and Kiani, 1985: 35).

Although blue and white pottery became common in the late 14th century in China and exported to Iran and other places while were imitated by Iranian potters, researchers believe that its technique was already in Iran and in the 13th century had gone to China. As the name of these dishes suggests, decorative blue on a white background is their characteristic. This type of ornament existed in Iran before Islam. In this regard, it can be said that examples of pottery with rare dark blue colors, on a blue-leaning background, have been obtained from the time of the Parthians and Sassanids by the Girshman expedition from Susa, and in fact, the Abbasid era can be considered as the period of revitalization of this technical method. (Rafi'i, 1998: 50) (Figure 6).

The Chinese became proficient in using blue and painted any design or pattern under glaze. This technique was completed during the Ming period (1363-1644). In fact, the blue and white containers of the Ming period were imported to the Middle East and caused the revival of this technique in Iran. These dishes were imitated by the Iranians. However, the remaining samples of blue and white dishes produced by Iranian potters were not very high quality.It was very similar, but it still lacked the desired look. Perhaps the reason for this is the lack of high-quality raw materials. They had a big problem and that was the lack of kaolin soil suitable for the white body of the dishes and decoration. It should also be noted that producing high-quality pottery or large pieces requires proper monitoring conditions for furnace fire.

Figure 6. Blue-and-white porcelain jug, early 15th century (Ming dynasty)

Source: The Trustees of the British Museum

At the end of the 8th century, with the Timurid coming to power, due to Timur's ambitions, friendly relations between Iran and China declined (MirJafari, 2018:591). After Timur died, his son Shahrokh took over the government. Shahrokh supported the business policy. His relationship with foreign courts increased the prestige of the Timurids and opened up trade routes with other nations. He established diplomatic relations and increased the volume of trade and exchanges. During his time, political and commercial relations between Iran and the Ming dynasty in China had a new and good period and this influenced the artistic relationship between the two countries.

Shahrokh sent the painter Ghiasuddin to China at the head of a delegation (Ajend, 2019: 732). He wrote an account of his journey and what he had seen in China. According to the sources and documents of this period, it can be concluded that relations between Iran and China have never been stronger than during the Shahrokh period. In the Timurid period, once again Chinese potters were influenced by Iranian metal forms and imitated them. From the remaining objects of this period, it can be assumed that metalworking in the Timurid period was prosperous. One of the special and common forms was the ewer with a bulging belly with an S-shaped handle that is shaped like a dragon. (Blair and Bloom, 2002:153-154)Blair and Bloom believe that its form can be traced back to metalworking in the early 13th century (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Bronze ewer

Source: Khalili Collections, UK, MTW 305

The potters of Jingdezhen produced wares to satisfy the demands of the Middle Eastern market like Iran. Large dishes were densely decorated with geometric patterns inspired by Islamic metalwork or architectural decoration. (Figure 8)

Figure 8. Bowl with geometric, floral, and epigraphic decoration

Source: Ashmolean Museum OXFORD

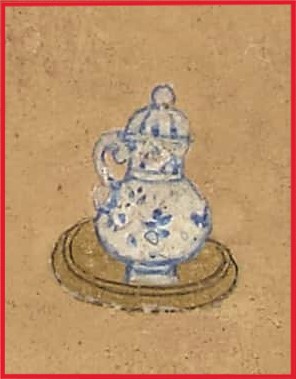

Blue-and-white porcelain was particularly admired by the Imperial court, and it is interesting to trace the shapes and motifs preferred by different emperors, many of whom ordered huge quantities of porcelain from the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen. The blue-and-white wares of the 14th and 15th centuries often took their shapes from Persian metalwork. The globular body, tall cylindrical neck and dragon handle of this jug all imitate the contemporary metalwork of Timurid Persia. (Vainker, The British Museum Press, 1991) The crowded decoration of this jug is a feature of early blue-and-white porcelain that continued into the early part of the Ming dynasty. It is very different to the generally more subtle character of Chinese ornament. There is no doubt that in the early Ming dynasty some of the most high-quality blue and white products were made with Iranian metal works Forms, though produced in general Chinese style. (Gary,1963:17)

However, the main Iranian example of this type of porcelain, which was the imitation pattern of Chinese pottery, is not available. There is only one broken ceramic jar in the Eleonora Spinnelein complex in Rome, which probably belongs to this category of dishes. This urn belongs to a group of Timurid objects whose production site can be attributed to northeastern Iran at that time and can be dated to the 15th century. The jar has a spherical body on a short ring-like base. The decoration of the painting is a blue underglaze on the white body. Two dragons opposite each other were drawn to the small body of the urn. It seems that the unusual shape of this ceramic belongs to the late 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century both in Iran and China. Contemporary metalworking may have an effect on the shape of this jar (Vittoria Fontana, 1996: 587), (figure 9)

Figure9. Blue-and-white ceramic jug

Source: Eleonora Spinnelein Collection, Rome Photographs by Tony Vatielli

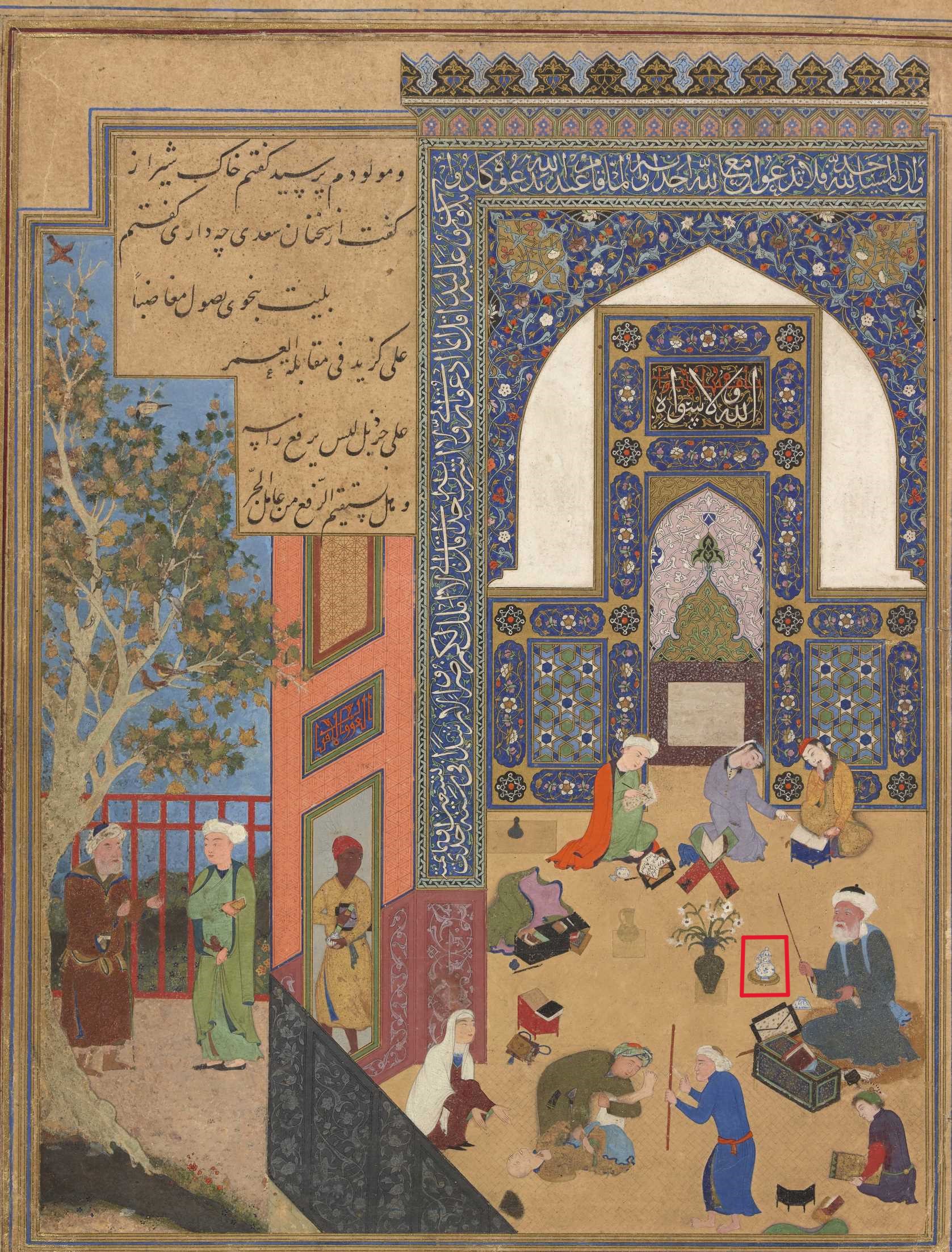

Also in one of the paintings attributed to Master Behzad can be seen as a blue and white dish, which indicates the prevalence of this form. (Figure 10) It could be said that Chinese artists began to imitate this form and produce blue and white pottery for Persian consumers. Blair and Bloom believe that This form was probably produced for export to markets outside of China and there is some valuable evidence to prove that they were sending such products to the Siraf Port in the south of Iran.

Figure 10. Sa'di and the Youth of Kashgar

Source: NationalMuseum of Asian Art, Washington, LTS1995.2.33

Conclusion

The communication and exchange of products between China and Iran have increased the interaction between the Culture and art in both countries. These effects can be seen both in the remaining documents and in the remaining artworks and products. Although the influence of Chinese pottery on Iranian pottery has been usually discussed before, as discussed in the paper, it can be said that Iranian art has also had a significant impact on Chinese pottery. During the examination of ceramics of China, clear signs of the influence of Iranian art can be observed in three characteristics of “products form”, “glazing techniques” and “ornamentation”, and the following results are stated:

1. Chinese artists took the most impressions of the Iranian metal container form, which is very evident in two historical periods and changed the form of Chinese dishes. The first influence in the Sasanian period is that Chinese potters imitated the silver ewer forms of Sassanid exported to China. In the Tang period, Persian common motifs and Sassanid art such as hunting scenes and legendary birds on pottery were depicted. These containers made in China were exported to Iran during the later dynasties of China.

2. The next stage of this effect is in the Timurid period of Iran, and the study of metalwork of this period makes clear that the famous metal container form of this period, the ewer with the dragon handle, has been precisely imitated by Chinese potters, one of which remains and it is believed that ceramic and pottery manufacturers in China produced these dishes specifically for export to the Iranian markets.

3. With the examinations there, we can say that the famous white and blue pottery of China is influenced by Iranian pottery. The first examples of this glazing technique existed in Iran before Islam. In the Seljuk period, A blue glazed ceramic was sent to China and started a new course of glazing technique. Even Chinese Handicraft men used cobalt which was imported from Iran. The arrival of Chinese Blue and White ceramics in the Timurid Period in Iran is The revival of this glazing technique in Iran.

References

1. Jaafarnia, Mohsen. 2015. Iran and China Relationship: Product Design Based on Cultural Needs.

2. Lotfi Batool, Akbari Abas, Javari Mohsen. 1394 The influence of Iranian art on Chinese pottery, Negareh, no35, 2015, P49-59

3. Azari, Aladdin. 1988, the history of Iran-China relations. Tehran: amirkabir

4. Wolf, Hans. 1993. Iran's old handicrafts. Tehran: Publication of learning Islamic revolution organization.

5. Daneshpoorparvar, Fakhri. 1994. Mutual Influence of Iran-China Art. Mirasfarhangi. No.12 P:44-47

6. Iranica. 2005. “Chinese-Iranian RelationsXIV. The Influence of Eastern Iranian Art”: iranicaonline.org/articles/chinese-iranian-xiv date:2014/06/06

7. Froom, Aimee. 2008. Persian Ceramics. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

8. Poop, Arthur Et. all 2008, magnum opus art of Iran. Tehran: Elmi-Farhangi

9. Nikkhah, Hanieh. And Ali sheikh, mehdi. 2010. An approach to Mongol cultural policies in Zarrinfam dishes. Islamic art studies. No31. P:109-126

10. Brand, Barbara. 2004. Islamic art. Tehran: Islamic art studies institution.

11. Rafie, Leila. 1998. Iran ceramic. Tehran: yasavoli.

12. Karimi, Fatemeh. And Kiani, Mohamad Yousef. 1985. Iran pottery art in the Islamic period. Tehran: archaeology Center of Iran.

13. Wilkinson, Charles. 2000. Paint and Design in Iranian Pottery. Tehran: agah: p. 133-149.

14. Fehervari, Geza. 2000. Ceramics of the Islamic World in the Tareq Rajab Museum. London: I. B. Tausis.

15. Fitz, Jerald. 1988. China culture history. Tehran: elmi-farhangi.

16. Mirkhand, Mohamad. 2001.History of Rozasafa, No.9-11. Tehran: asatir.

17. Mirjaefari, hosein. 2000. History of Political Social and Cultural Developments in Iran during the Timurid Period. Tehran: samt.

18. Azhand, yaghoub. 2010. Iran painting, no.1. Tehran: samt.

19. Beller, shila. And bloom, Jonathan. 2002. Iran Islamic art and architecture. azhand, yaghoub. Tehran: samt.

20. Gary, Basil. 1963. Persian Influence on Chinese Art from the Eighth to the Fifteenth centuries. British Institute of Persian Studies,p. 13-18.

21. vitoria Fontana, maria. 1996. “ABlue-And-White Timurid Jug withtwo Confronting Dragons”, Istituto per l,Oriente C. A. Nallino, p. 587-600The Ashmolean Museum: ashmolean.org

22. Lentz, W. Thomas & Glenn D. Lowry, 1989, Timur And The Princely Vision: Persian artand culture in the fifteenth century.

23. Mahler, Jane Gaston. 1959. Westerners Among the Figurines of the Tang Dynasty ofChina, Rome.

24. JunLiu and Lei Wu, 2010. Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies in Asia Vol.4 No.1

25. Feng T. (1996). Diplomatic History of China. Wuhan: Hubei People’s Publishing House.

26. Wood, F. (2004). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. Berkeley:University of California Press.

27. Garver, J. (2007). China and Iran: Ancient Partners in a Post-imperial World.Seattle: University of Washington Press.

![]()

© 2023 by the authors.

Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).